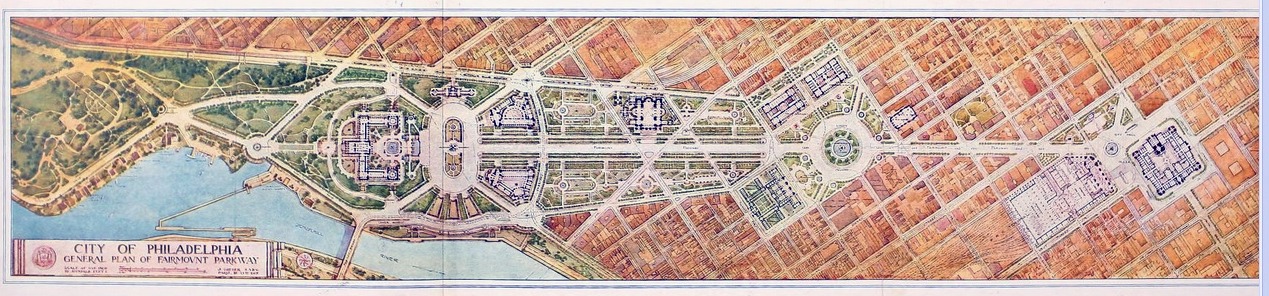

BRITISH CLASSICISM

Reading a recent monograph on the work of John Simpson, I am struck again by the difference between American and British classicism. For one thing, the former is rooted in a much shorter tradition. Moreover, it is a tradition that is, in a sense, academic. Or, at least bookish. In the first instance it derived from (British) pattern books, which were the main source of information for the early colonial builders. Nineteenth-century American classicism, on the other hand, was chiefly the product of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where many American architects of that period were trained. Although there were many talented self-taught architects such as Stanford White,

I never attended any of Vincent Scully’s legendary Yale architecture classes but I did hear him speak several times in Montreal, part of the Alcan lecture series that Peter Rose organized in the 1970s. So I could understand when people spoke of his influence. Scully introduced a Celtic passion to the sometimes dry subject of architectural history and his lectures were bravura performances that brought old buildings—and their builders—to life. He was an activist historian in the mold of Siegfried Giedion, and he influenced the contemporary scene, being an early advocate of the work of Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi.

I never attended any of Vincent Scully’s legendary Yale architecture classes but I did hear him speak several times in Montreal, part of the Alcan lecture series that Peter Rose organized in the 1970s. So I could understand when people spoke of his influence. Scully introduced a Celtic passion to the sometimes dry subject of architectural history and his lectures were bravura performances that brought old buildings—and their builders—to life. He was an activist historian in the mold of Siegfried Giedion, and he influenced the contemporary scene, being an early advocate of the work of Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi. What’s with all the black houses that have appeared in recent years? The all-black exteriors—blackened timber, black stain, or simple black paint—have become ubiquitous. Rural or urban, even old buildings are getting black-faced. Traditionally, architects avoided black facades, which not only look lugubrious but virtually eliminate shadows, which are—or were—one of the architect’s most effective tools. Modern houses tend not to have moldings and relief work, of course, so there are no shadows. And black does seem to be the modernist architect’s favorite fashion shade (Richard Rogers excepted). But fundamentally I think this phenomenon is a symptom of laziness—it’s a cheap way of standing out.

What’s with all the black houses that have appeared in recent years? The all-black exteriors—blackened timber, black stain, or simple black paint—have become ubiquitous. Rural or urban, even old buildings are getting black-faced. Traditionally, architects avoided black facades, which not only look lugubrious but virtually eliminate shadows, which are—or were—one of the architect’s most effective tools. Modern houses tend not to have moldings and relief work, of course, so there are no shadows. And black does seem to be the modernist architect’s favorite fashion shade (Richard Rogers excepted). But fundamentally I think this phenomenon is a symptom of laziness—it’s a cheap way of standing out. We recently replaced a kitchen faucet. The product is a typical example of globalization. The ceramic cartridge—the soul of a faucet—is made in Hungary, the aerator comes from Italy, and the rest of the faucet was manufactured and assembled in China. The company that markets the faucet, despite its name—Kräus—is not German but American, based on Long Island. I believe that the design is American, too, although the inspiration is German. It reminds me of the door and window handles that Walter Gropius designed in 1923. By the way, it’s an excellent faucet.

We recently replaced a kitchen faucet. The product is a typical example of globalization. The ceramic cartridge—the soul of a faucet—is made in Hungary, the aerator comes from Italy, and the rest of the faucet was manufactured and assembled in China. The company that markets the faucet, despite its name—Kräus—is not German but American, based on Long Island. I believe that the design is American, too, although the inspiration is German. It reminds me of the door and window handles that Walter Gropius designed in 1923. By the way, it’s an excellent faucet. Aaron Betsky

Aaron Betsky