Reading a recent monograph on the work of John Simpson, I am struck again by the difference between American and British classicism. For one thing, the former is rooted in a much shorter tradition. Moreover, it is a tradition that is, in a sense, academic. Or, at least bookish. In the first instance it derived from (British) pattern books, which were the main source of information for the early colonial builders. Nineteenth-century American classicism, on the other hand, was chiefly the product of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where many American architects of that period were trained. Although there were many talented self-taught architects such as Stanford White, Ralph Adams Cram, Bertram Goodhue, and Horace Trumbauer, the leading figures—Richard Morris Hunt, Charles McKim, John Russell Pope, and Thomas Hastings—were EBA alumni, and brought a correct and sometimes rather dry approach to classicism. This is in contrast to nineteenth-century British classicism, which was not based in the academy but in practice. The influence of architects such as John Nash, John Soane, and C. R. Cockerell is evident in Simpson’s designs which are more self-assuredly original than those of many of his American contemporaries which can be often more concerned with correctness than with invention. It is also, interestingly, often more urban, as in this photo (below) of a new residential development along Old Church Street in London’s Chelsea.

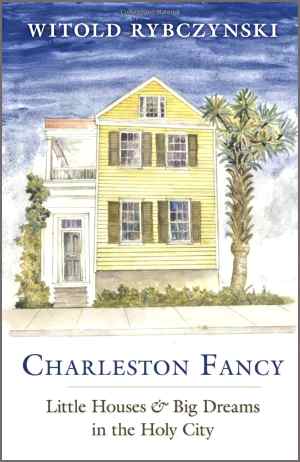

Photo: Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace (John Simson, arch.)