WRIGHT WAS RIGHT

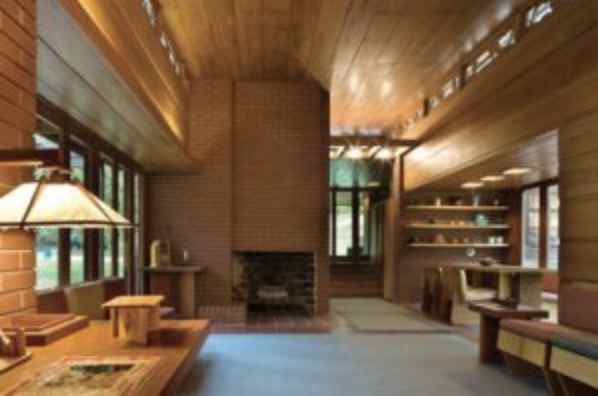

Ian Bogost’s excellent Atlantic article on the fashionable open plan, which integrates the kitchen into the main living spaces of the house, points out the drawbacks of this arrangement: leaving a messy kitchen open to full view, which can be awkward when entertaining. Bogost correctly credits Frank Lloyd Wright with popularizing the open plan, but he doesn’t point out that in Wright’s Usonian houses, the kitchen—which he called the workspace—is generally positioned out of view of the living room. In this photograph of the Pope-Leighey House, a small Usonian built in 1941 in suburban Virginia, the compact kitchen is unobtrusively tucked in behind the brick wall containing the fireplace. Conveniently opposite the dining area, but out of view. This arrangement is vastly superior to the modern practice of exposing the kitchen as if it were a stage set, which, with all those expensive stainless steel “commercial” appliances prominently on display, I suppose it is.

Incidentally, the Pope-Leighey House now sits on the grounds of Woodlawn Plantation in Alexandria, Virginia and is open to the public.

TOM WOLFE (1930-2018)

The first time I heard Tom Wolfe speak in public was in 1965 or ’66. I was a student at McGill University where he had come to lecture. One line has stuck in my memory; he compared himself to the “renegade cowboy,” the character in Western movies who has lived with the Indians and who comes back to town to tell the tale. I knew Wolfe’s writing from reading him in Esquire, and The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby may have been out by then. I remember From Bauhaus to Our House (1981) which came out first as an article in Harper’s (July 1981). By then I was working on minimum cost housing research, somewhat estranged from high architecture, so I had no objection to his mocking tone. I had not yet experienced the epiphany that came from writing Home, but I thought his take on the Modern “revolution” rang true. I still do. Judging from Twitter, From Bauhaus to Our House still rankles architecture critics, as it was intended to do. How could someone not admire the Seagram Building? Almost 40 years later, as Yale University spends half a billion dollars building two Gothic Revival colleges,

PRESERVATION

Why do we renovate, restore, or otherwise preserve old buildings after they have become functionally obsolete? One reason is practical—the building is in good enough shape to be still useful, even in an altered state, or for a different purpose than originally intended. The second reason is cultural. Perhaps the building was once the home of an important figure—Mozart’s house in Vienna, for example, or Washington’s Mount Vernon—or maybe it was the site of an important event such as the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The third reason is aesthetic: the building is beautiful and incorporates artistry and craftsmanship that have made it the object of our affection. This applies to grand monuments, but also to buildings of lesser ambition; there are entire neighborhoods that represent important human achievements. What seems to me a less compelling reason is the idea that a building should be preserved simply because it is representative of a previous period or architectural fashion. In architecture, as in many human endeavors, not all periods are equally admirable; there are ups and downs. I do wish that masterpieces such as Richardson’s Marshall Fields Wholesale Store, McKim’s Penn Station, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building had not been demolished,

A MAN OF INFLUENCE

“But an influence is not necessarily a good influence” writes Joan Acocella in a review of books about Bob Fosse. She’s right, of course. How often we describe an architect as influential, without qualifying the nature of that influence. Probably the most influential American architect of the late nineteenth century was H. H. Richardson—Richardsonian Romanesque libraries and courthouses grace cities and towns across the country. It’s hard to go wrong with this style. The only modern architect to give his name to a style was Mies van der Rohe, but his legacy is less certain. In the hands of faithful acolytes like SOM, the influence could be benign, but the scores of banal steel-and-glass boxes and miles of appliqué I-beams attest to the limitations of the minimalist Miesian approach. Michael Graves was another architect whose influence was not necessarily “good.” Without his refined color sense and knowledge of history, postmodern practitioners produced parodies—weak jokes without punch lines. Louis Kahn was the most important modernist architect of the late twentieth century, but his influence on American architects was negligible; his “philosophy” was too obscure, and his building forms too distinct to comfortably imitate. Or at least so it seemed to me before I visited India.

FUTURE SHOCK

One of the first buildings expressly intended to grow was the main library of the University of Pennsylvania, which opened in 1891. Frank Furness designed a head-and-tail building, with a magnificent four-story reading room as the head, and the stacks as an ever-expanding tail. The three-story stacks housed 100,000 books, but the end wall was removable so that the stacks could be extended, bay by bay—up to three times their length—increasing their size and capacity. Furness was correct about the need to accommodate more books, but he was wrong about the expansion. In 1915, the university erected an unrelated building on the site of the future stacks, effectively blocking his long-sighted vision. This has been the fate of many such future-oriented designs. It isn’t that buildings aren’t added on to, but the additions are generally ad hoc, not following any predetermined plan. This was even true in the 1970s, when architects were fascinated by the idea of growth. Norman Foster’s Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts was a linear shed intended to grow at either end, but when the building was expanded (by Foster!) it ignored this strategy and went underground instead. I think the problem is a combination of practicality and hubris.

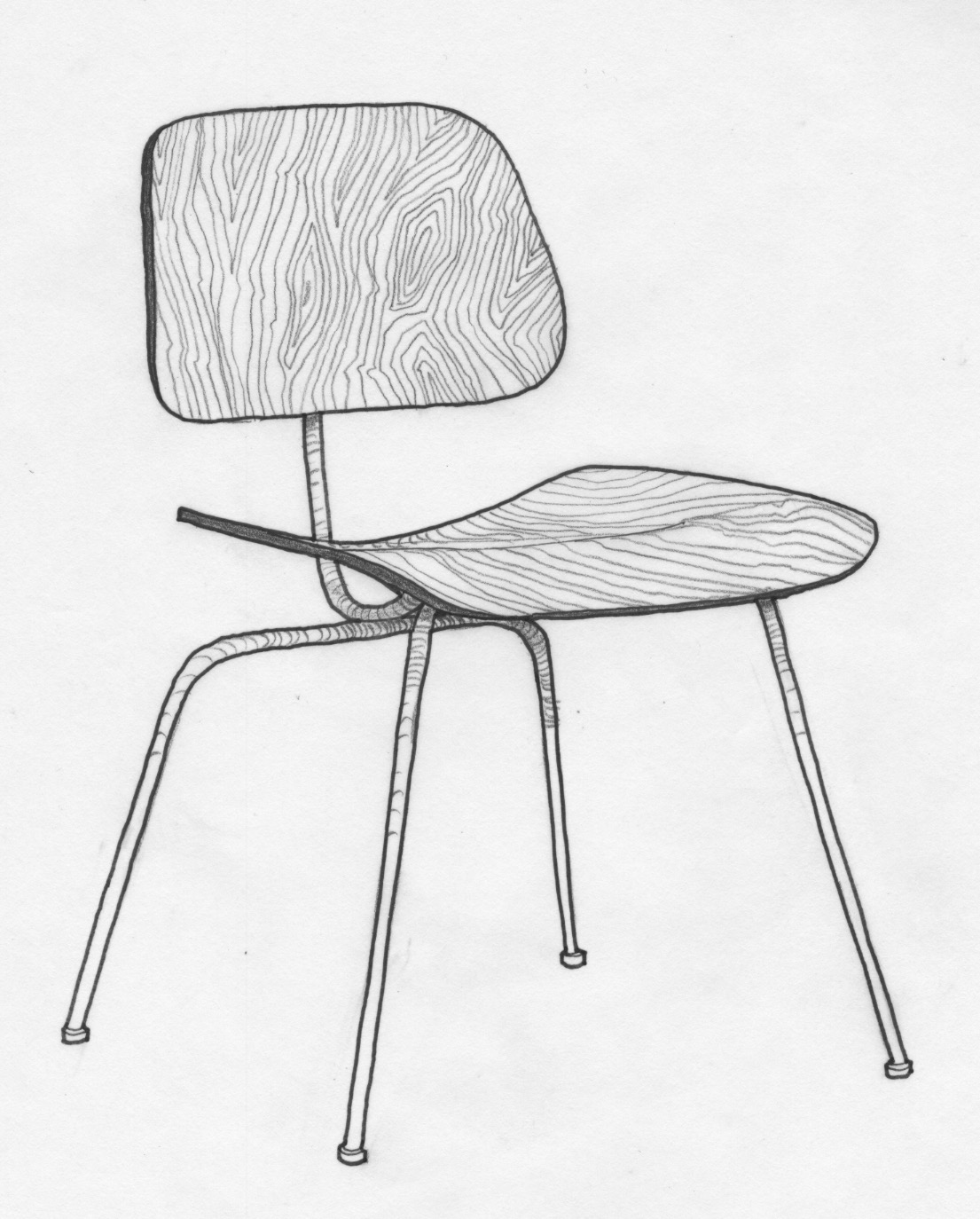

DESIGN AND RESEARCH

A recent article in Architect quoted Jérôme Chenal, a Swiss architecture professor: “Design is not research, that is just speculation . . .” Exactly so. For years I have heard design studio teachers maintain that what they do with their students qualifies as research, and that it is an injustice that it is not recognized by the rest of the university as such. But Chenal is correct, design is speculation, not research. There is no real feedback. I suppose if a design were built and evaluated it might qualify as a sort of research, but studio work remains on paper—or, rather, on the screen. Feedback, in the form of the comments of critics, is a function of taste rather than performance data. The same is true in the profession. The practice of architecture is ill-suited to research—clients do not expect to pay for experiments, they want buildings that work. This is not to belittle design, but rather to distinguish it from research. When Charles and Ray Eames laboriously developed a technique for heat-forming wood laminations into three-dimensional shapes, that was research. When they produced the DCM chair, the “potato-chip chair,” that was design.