THE LAYERS OF THE PAST

Ian Volner’s review of Robert A. M. Stern’s Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia is more even-handed that Inga Saffron’s mean-spirited screed in the Inquirer. But both critics miss an important aspect of Stern’s design: its relation to the nearby U.S. Custom House. That 17-story tower is the most prominent building in the area and provides a backdrop to the museum, evident in Peter Aaron’s evocative photograph. The museum echoes some of the brick and limestone details, as well as the crowning lantern. The Custom House, a WPA project completed in 1934,

Ian Volner’s review of Robert A. M. Stern’s Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia is more even-handed that Inga Saffron’s mean-spirited screed in the Inquirer. But both critics miss an important aspect of Stern’s design: its relation to the nearby U.S. Custom House. That 17-story tower is the most prominent building in the area and provides a backdrop to the museum, evident in Peter Aaron’s evocative photograph. The museum echoes some of the brick and limestone details, as well as the crowning lantern. The Custom House, a WPA project completed in 1934,

There is a long tradition of architectural research in structures—one thinks of Nervi, Candela, Torroja, and Frei Otto, the pioneers of concrete like Perret, and much earlier the Byzantine and Gothic builders. Architects have sometimes experimented successfully with new building techniques and materials (Rudolph invented striated concrete blocks; Foster was the first to use structural glass fins). But research into how people use buildings is rare. The profession has always recognized the value of so-called post-occupancy evaluation, and the need for knowledge based on how people actually behave in and use buildings. The problem has been that this kind of research is extremely complicated,

There is a long tradition of architectural research in structures—one thinks of Nervi, Candela, Torroja, and Frei Otto, the pioneers of concrete like Perret, and much earlier the Byzantine and Gothic builders. Architects have sometimes experimented successfully with new building techniques and materials (Rudolph invented striated concrete blocks; Foster was the first to use structural glass fins). But research into how people use buildings is rare. The profession has always recognized the value of so-called post-occupancy evaluation, and the need for knowledge based on how people actually behave in and use buildings. The problem has been that this kind of research is extremely complicated, Is every building made out of concrete automatically Brutalist? The answer is yes, according to a recent

Is every building made out of concrete automatically Brutalist? The answer is yes, according to a recent  Norman Foster is building an office building in downtown Philadelphia. The Comcast Innovation and Technology Center, a 1,121-foot skyscraper, will be the tallest building in the city. Passing by the other day, I noticed elevator cabs scuttling up and down the side of the building. They reminded me of the external elevators on the Pompidou Center in Paris. Typical High Tech detail, I thought to myself, before I realized that these were construction elevators. The actual core is deep inside the building in the conventional fashion. And unlike Foster’s Hongkong & Shanghai Bank building, the structure is concealed as well (except for a vestigial expression of cross bracing on the otherwise pristine glass facade).

Norman Foster is building an office building in downtown Philadelphia. The Comcast Innovation and Technology Center, a 1,121-foot skyscraper, will be the tallest building in the city. Passing by the other day, I noticed elevator cabs scuttling up and down the side of the building. They reminded me of the external elevators on the Pompidou Center in Paris. Typical High Tech detail, I thought to myself, before I realized that these were construction elevators. The actual core is deep inside the building in the conventional fashion. And unlike Foster’s Hongkong & Shanghai Bank building, the structure is concealed as well (except for a vestigial expression of cross bracing on the otherwise pristine glass facade). Isabella Lobkowicz kindly sent me a copy of her recent book, Almost 100 Chairs for 100 People. “It’s curious how many designers design chairs,” she writes in the Foreword, “but nobody seems to think about the characters who are going to use them.” Princess Isabella (she is married to a Bohemian prince) rectifies this situation with a delightful sketchbook—published by

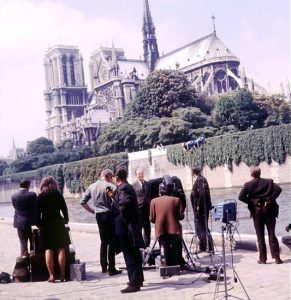

Isabella Lobkowicz kindly sent me a copy of her recent book, Almost 100 Chairs for 100 People. “It’s curious how many designers design chairs,” she writes in the Foreword, “but nobody seems to think about the characters who are going to use them.” Princess Isabella (she is married to a Bohemian prince) rectifies this situation with a delightful sketchbook—published by  I’ve been watching Civilisation, the 1969 BBC television series, on YouTube. It’s a refreshing experience, and a reminder of how much the documentary film form has been influenced—I almost wrote infected—by Ken Burns. Instead of a revolving door of talking “expert” heads Civilisation makes do with a single presenter. There are no voice-overs pushing a narrative along, no actors dramatizing, no staged sequences, instead we have the wise (and rather dapper) Kenneth Clark to guide us. The 13-part series is subtitled “A Personal View,” and that is one of its strengths. Clark, an art historian,

I’ve been watching Civilisation, the 1969 BBC television series, on YouTube. It’s a refreshing experience, and a reminder of how much the documentary film form has been influenced—I almost wrote infected—by Ken Burns. Instead of a revolving door of talking “expert” heads Civilisation makes do with a single presenter. There are no voice-overs pushing a narrative along, no actors dramatizing, no staged sequences, instead we have the wise (and rather dapper) Kenneth Clark to guide us. The 13-part series is subtitled “A Personal View,” and that is one of its strengths. Clark, an art historian, Writing a

Writing a