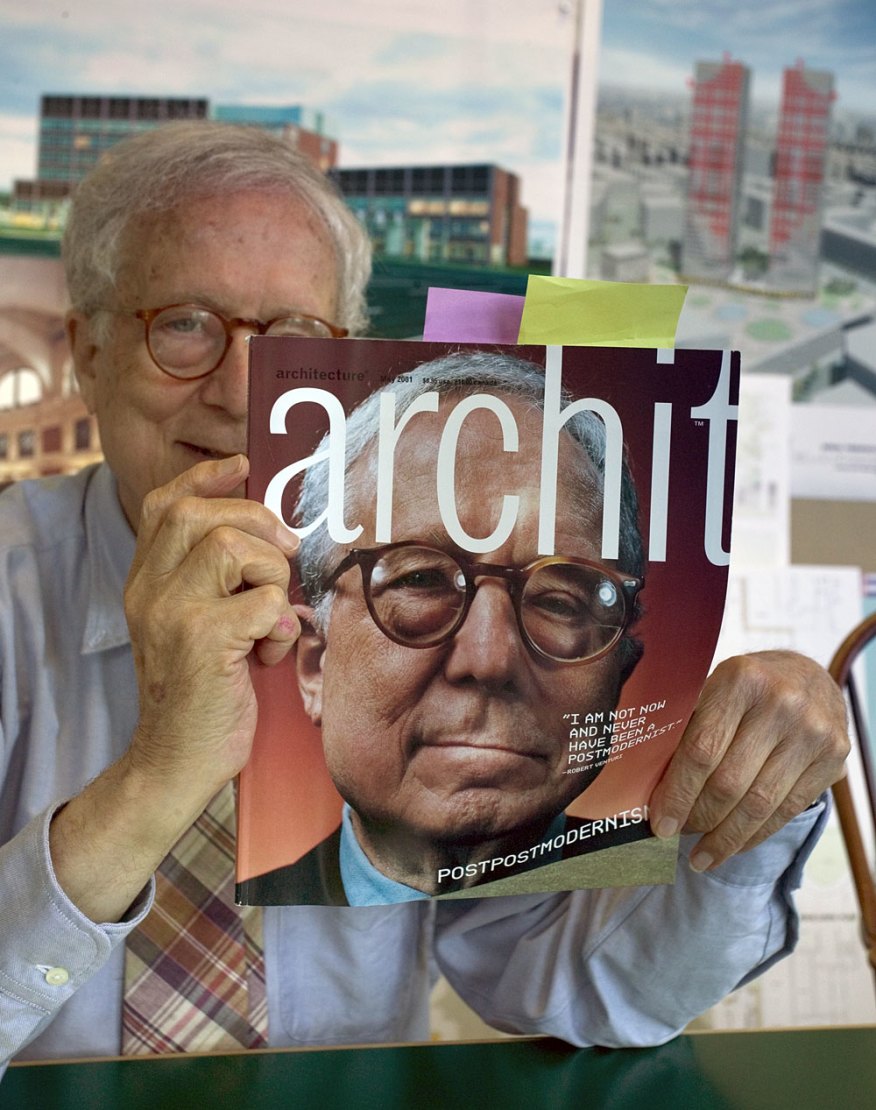

“I am not now and never have been a postmodernist,” said Robert Venturi twenty years ago; the quote appeared on the cover of the May 2001 issue of Architecture. But of course he was a postmodernist, although it is no wonder that he wanted to disassociate himself from that movement; after several decades PoMo had run its course, moreover in hindsight it appeared that it had done more harm than good. The best postmodernists had produced first-rate work—the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, the Sainsbury Wing in London, the Beverly Hills Civic Center—but few architects were as historically knowledgable as James Stirling, Venturi, and Charles Moore—and in less capable hands PoMo was thin gruel indeed: an unconvincing blend of ersatz history and weak-kneed modernism. It’s easy to ridicule postmodernism today, but it is worth remembering what it was reacting against: lumbering Brutalism, warmed-over Mies, inept minimalism. Stirling was critical of modernist conventions: “The language itself was so reductive that only exceptional people could design modern buildings in a way that was interesting.” Postmodernism ultimately proved a failure as a broad-based movement—it turned out that only exceptional people could design interesting postmodern buildings, too. In that regard, it was much less successful than earlier short-lived architectural episodes such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco.