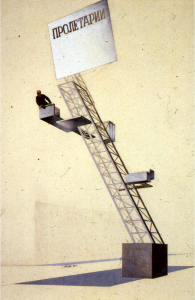

I’ve been reading David Watkin’s Morality and Architecture and I’m struck by the parallel that he draws between modernism and totalitarianism. Now, the conventional story, told and re-told by advocates of the International Style, was that modernist architecture was a moral force, not only opposed to (bad) nineteenth-century Beaux Arts architecture, but also to Nazism and Fascism. This claim was lent credence by the fact that so many leading modernists—Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Eric Mendelsohn, Marcel Breuer—had fled Nazi Germany. That Le Corbusier happily offered his services to the rightist Vichy regime in France, that Philip Johnson was sympathetic to the National Socialists, and that Mussolini’s Italy sponsored some excellent modernist architecture, did not tarnish the story. Modernism was on the right side: progressive, transparent, clean, unsullied by history. Watkin writes that, quite the opposite, collectivist modernism had a deep totalitarian streak. “The individual is losing significance,” Mies wrote in 1924, “his destiny is no longer what interests us.” Le Corbusier, that other great figure of modernism, likewise saw an impersonal future where houses would be machines for living in. “The denial of the role of the individual as a creative or significant force, and the belief that his role is that of a mere voice through which the great unconscious consensus of the age can be expressed, are ideas familiar in nineteenth- and twentieth century political philosophy,” Watkin writes. Of course, the early modernists were architects not philosophers, and like so many architects they were primarily interested in getting their own way, so much of the deterministic appeal to the zeitgeist was little more than ex post facto rationalization. But isn’t that always the way with architectural theory?