OUR SHINY FUTURE

I attended a neighborhood association meeting last night to hear about a proposed apartment building: 2100 Hamilton Street in the Benjamin Franklin Parkway area of Philadelphia. The “review” was a matter of courtesy on the part of the developer since he had just received his building permit from the city. The animated questions from the audience concerned practical issues: how would traffic be handled, would the building block views, would the developer repair the broken sidewalk, where would visitors park. In truth, the 10-story condominium with only 33 units would not be a major burden on the neighborhood. Sadly, nor would it be much of an adornment. The nineteenth and early twentieth century residential architecture of downtown Philadelphia is a rich visual feast that provides many pleasures to the passerby, whether the building is a modest rowhouse, an apartment building, or a renovated factory. The richness is a result of the materials and ornamental details: a decorated door surround, a cast-iron curlicue, a fanciful gable. 2100 Hamilton Street exhibits none of these features. Briefly put, like almost all new buildings in downtown Philadelphia, it is a glass box. Nothing but glass, except for some rather grim metal panels on the north side.

HE SAID, SHE SAID

The finding of a recent online poll by AJ contrasts the views of architects (about a third of the respondents) with those of the non-professional public. The participants were shown images of housing, some traditional, some Modern. The public favored the former and the professionals the latter. In itself, a disconnect in opinion is not unexpected; trained professionals might appreciate attainments that are not immediately obvious to the unskilled eye. But the difference here was not one of nuance, what the architects admired was actually held in low esteem by the non-architects, and vice versa. “To the best of our knowledge the ‘winners’ of our poll (some houses in Poundbury) have not won any architectural awards; indeed they are widely reviled by the profession. The two losers have won nine between them.” The AJ article also describes an earlier—more structured—survey. “A group of volunteer students were shown photographs of unfamiliar people and buildings and asked to rate them in terms of attractiveness. Some of the volunteers were architects; some were not. As the experiment progressed, a fascinating finding became clear: while everyone had similar views on which people were attractive, the architecture and non-architecture students had diametrically opposed views on what was or was not an attractive building.” The research referred to was conducted in 1987 by David Halpern.

THE HIGH COST OF HIGH TECH

The Philadelphia Inquirer reports that the Comcast Technology Center is running $67 million over budget. The 60-story Technology Center (Foster + Partners), currently under construction next to the 58-story Comcast Center (Robert A. M. Stern Architects), is a very expensive building: $1.5 billion versus $540 million for the latter. The Comcast Center was completed ten years ago, so that makes a difference, and the Tech Center will include a 12-story Four Seasons hotel. But the amount of office space is virtually identical, 1.3 million square feet, compared to 1.25 million square feet in the older building, although the Tech Center is designed for greater planning flexibility. It would appear that high-tech architecture—and longer spans—simply cost more.

Photo: Comcast Tech Center (left) and Comcast Center (right).

A BRIDGE TOO FAR

Reading about Venice’s new Ponte della Constituzione I was reminded—again—of the dangers of architectural experimentation. The bridge, designed by Santiago Calatrava, is full of novelty: irregular steps, illuminated glass treads, and a beautiful but very flat arch. All these innovations have created problems. The irregularly-dimensioned steps cause people to trip, steps make the bridge inaccessible to wheelchairs (a strange-looking mechanical pod has been added), and the flat arch has created structural stresses on the foundations. As for the glass treads—they become slippery when wet, and the glass gets chipped by tourists wheeling their luggage, requiring expensive replacement. To make matters worse, the bridge cost three or four times more than estimated—a Calatrava trademark. No wonder the city of Venice is suing the architect. But the greater wonder is that clients still commission “ground-breaking” and “unprecedented” designs. Surely they would have learned their lesson by now? Beware of architects bearing shiny new gifts, whether in terms of untested materials, new technologies, or unusual solutions. There is a reason that architecture is—or at least traditionally was—the most conservative of the arts. Buildings last a long time—hundreds of years—and old buildings are the best evidence of what passes the test of time.

STREETSCAPE

Passing the entrance to 10 Rittenhouse Square on 18th Street in Philadelphia today I was caught up short. Robert A. M. Stern Architects, who designed the 33-story apartment tower, have done something cunning. The entrance to the tower is distinctly low key, a simple break in a low stone wall, flanked by two piers topped by stone balls. Beyond the break, a short path leads to a glass marquee over the front door. It was the wall that interested me. 10 Rittenhouse Square’s immediate neighbor is the Fell-Van Rensselaer mansion, designed in 1898 by the great Boston firm, Peabody & Stearns. The Indiana limestone exterior is rather grand. The new limestone wall, which significantly overlaps the two properties, gives the impression that it was originally a part of the mansion. Thus the entrance to number 10 becomes integrated with its older neighbor, despite the fact that the apartment tower itself is brick, not limestone, and does not exhibit similar architectural features. A very nice detail.

INTUITION

“Intuition has to lead knowledge, but it can’t be out there on its own,” said Bill Evans. “If its on its own, you’re going to flounder sooner or later.” He was speaking to Marian McPartland during a 1979 appearance on her NPR show, Piano Jazz. Evans was talking about the need to respect the basic structures of music, but it struck me that what he said applies equally to architecture. Especially today. Intuition seems to drive design; having set aside knowledge, that is, history, architects are winging it. And, yes, there is much floundering.

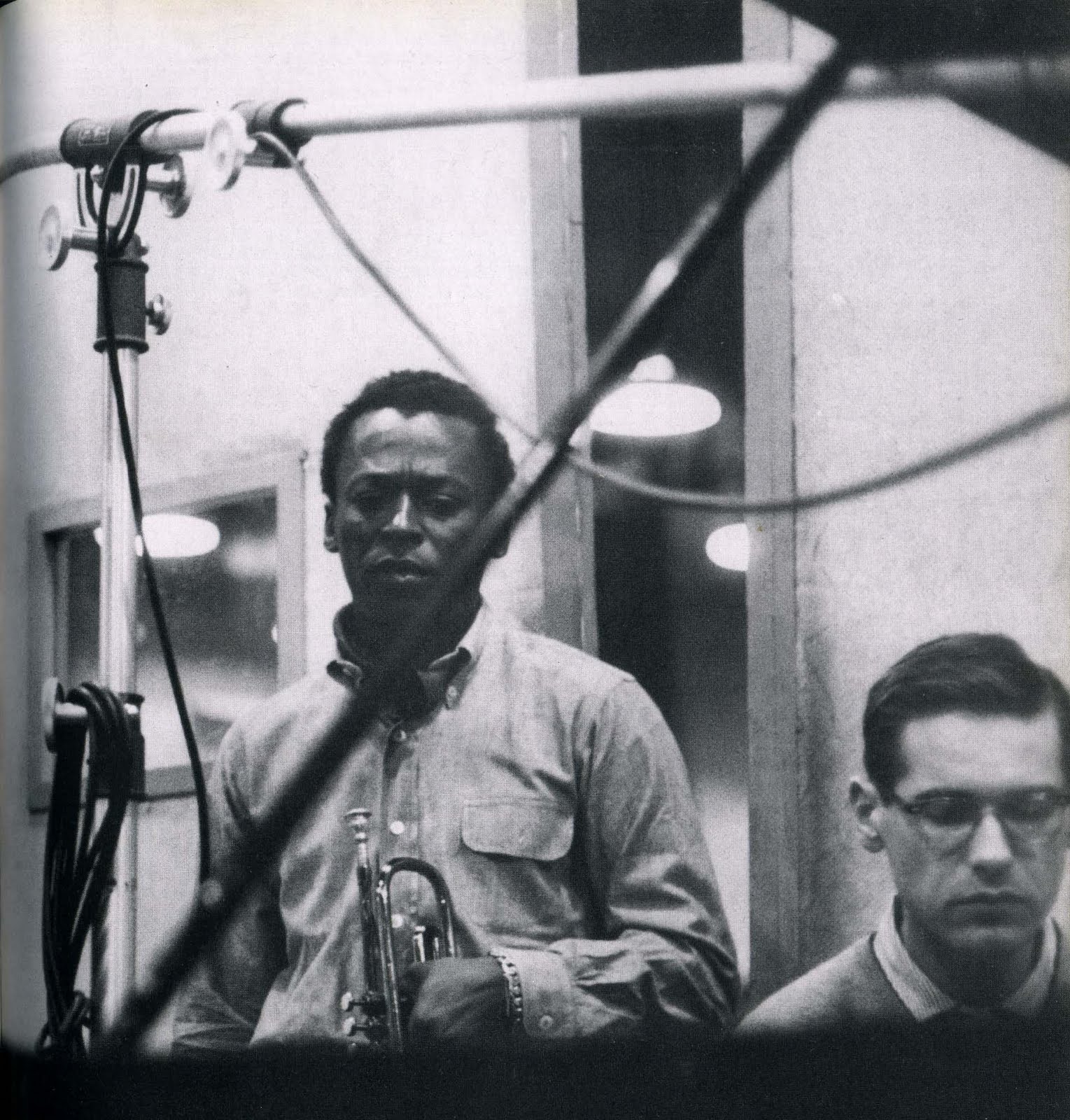

Photo: Bill Evans and Miles Davis, late 1950s.