FRUITCAKE

What is it with Americans and fruitcakes? For many years we used to throw an annual midday New Year’s Day party. Bloody Marys, big buffet table, Niman Ranch ham, stuff like that. People seemed to enjoy the food, but we noticed that there was usually leftover fruitcake. We were puzzled why there were so few takers, because we had gone to a lot of trouble to order this particular confection from Vermont. Perhaps because we came from Canada, where fruitcake—dark, moist, and rich—is a Christmas tradition, we didn’t know that to Americans fruitcake was associated with a different tradition. According to Wiki, “the fruitcake had been a butt of jokes on television programs such as Father Knows Best and The Donna Reed Show . . . and appears to have first become a vilified confection in the early 20th century, as evidenced by Warner Brothers cartoons.” According to Wiki again, there is a town in Colorado that hosts something called the Great Fruitcake Toss on the first Saturday of every January, using recycled—that is, uneaten—fruitcakes. No wonder so many of our guests gave our fruitcake a pass. We stuck to our guns and continued to serve fruitcake (with cheese,

LOOKING NORTH

I attended McGill University, which is sometimes described as “the Harvard of the North.” After reading Ross Douthat’s column on the Ivy League in today’s New York Times, it’s evident that it really isn’t—or at least wasn’t when I was there. One difference is that Canadian students didn’t “go away to college,” they simply attended whatever university was near to where they lived. Thus, most of my architecture classmates—all men—were Montrealers. Unlike Ivy League campuses today, which are awash with monogrammed sweatshirts and caps, we didn’t show off our affiliation—actually we didn’t wear sweat shirts, rather jackets and ties, and in the 1960s the annoying fashion for baseball caps had not yet taken hold. Another difference was that Canadian university tuition was not exorbitantly high. (The very wealthy had the option of sending their kids to the US.) Thus, my classmates were resolutely middle-class, mostly WASPs, a handful of Jewish Montrealers, a sprinkling of immigrant kids like myself, and a token French Canadian (they tended to go to the Université de Montréal). Did I drink? Yes, a lot, at least in the early years; late nights in the architecture studio eventually put a crimp into that activity.

IN THE CORNER WITH MAURY

Richard Terrill recounts a wonderful story in “Who Was Bill Evans?”

Jazz bandleader Stan Kenton told a story about himself as a kid, trying to sneak into a Paris club to hear jazz. He was too young to drink, even in France. The concierge finally said, ok, just go sit in the corner with that old man. His name is Maury.

And it went like this for several evenings. Go sit in the corner with Maury, kid.

Years later, Kenton learned that the old man had been Maurice Ravel.

POP GOES THE WEASEL

News that the Abrams House in Pittsburgh, designed by Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown in 1979, has been sold and is to be demolished. Apparently, the new owner, who lives in the adjacent Giovannitti House (designed by Richard Meier) wants to enlarge his garden—the original owner of the Giovannitti House had sold the back part of his lot to the Abrams. Or maybe he just wanted to get rid of an eyesore? Venturi’s postmodern antics do not age particularly well. I was struck by the presence of a large (looks to be about 8 feet by 12 feet) painting by Roy Lichtenstein in the Abrams living room. Lichtenstein (1923-97), was the premier Pop artists of that epoch; a painting of his sold in 2011 for a record $43 million. I assume that the Pittsburgh Lichtenstein was not included in the house sale, which netted a paltry $1.1 million. Apparently Pop art is more in demand than Pop architecture.

A CALM IN THE STORM

“Modernism wasn’t just a style—it was a way of thinking, a way of life,” expounds Jessica Todd Smith in a video on the Philadelphia Museum of Art website. Smith, who is the curator of the current PMA show, “Modern Times: American Art 1910-1950” (on view until September 3), also refers to the “beautiful chaos of innovation.” Those four decades were, indeed, chaotic: two world wars, the Soviet revolution, the Great Depression, social upheavals, the emergence of mass production and the consumer society. Where did this stormy time leave the artist? Adrift, judging from this show. Museums don’t pipe-in music (except in the gift shop), but if they did Cole Porter’s “Anything Goes” (from a 1932 musical of the same name) would be perfect. Innovation was the order of the day: Calder’s wire mobiles, O’Keefe’s enlarged lilies, Pollock’s frenetic daubing. “The world’s gone mad today. And good’s bad today.” It’s a relief to come across Horace Pippin’s calm portrait of Christian Brinton (1940), a supportive art critic. Calm, too, are Edward Hopper’s studies for his etching, American Landscape (1920). The work of photographers tends to be likewise distinctly un-frenetic, perhaps because shooting (especially with a large format camera), developing,

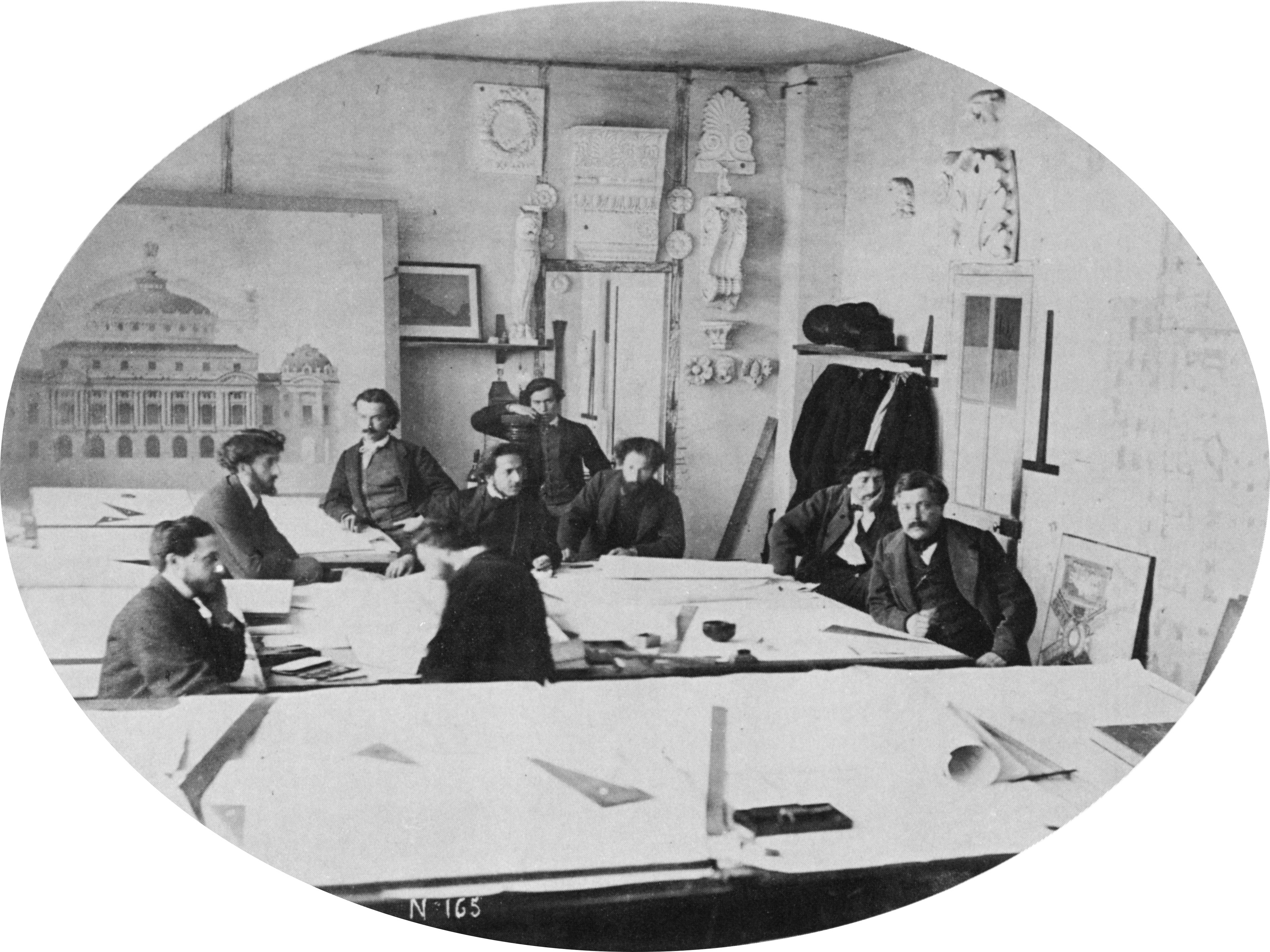

PAPER BLINKERS

The first university architecture programs appeared in the late nineteenth century, at MIT (1865) and the University of Pennsylvania (1868). Previously—and for a long time thereafter—most architects in the English-speaking world learned their craft through apprenticeship, on the job, working in an office. Frank Lloyd Wright, Edwin Lutyens, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Charles A. Platt, Horace Trumbauer, Ralph Adams Cram, and Bertram Goodhue are prominent examples. While it is still theoretically possible to become a registered architect through apprenticeship, in practice formal education has taken over the training of architects. How does one teach someone to be an architect? Since architecture is not a science, there is no underlying body of knowledge to absorb. Architects study precedents, but learning to design is like learning how to swim, you have to jump in the water. Hence, the studio system. Students are assigned building problems—simple at first, increasingly more complex—and develop solutions in drawings and models. These are evaluated by the teacher and invited “jurors”; the term is apt since student are required to “defend” their designs in public. The process is intended to simulate an actual building commission in the sense that there is a list of functional requirements and an actual building site,