GUESS WHERE?

by elementor | Mar 22, 2023 | Architecture

My friends Nancy and Randy Williams sent me this photo taken recently at the Villa Witold in Charleston, SC. The villa, inspired by the loggia of Palladio’s Villa Saraceno, was built in 2011 by Reid Burgess, George Holt, and Andrew Gould. Palladio built the original in 1548 outside Finale de Agugliaro, a small town in the Veneto. Described in detail in Charleston Fancy: Little Houses & Big Dreams in the Holy City.

DOUGLAS KELBAUGH (1945-2023)

by elementor | Mar 9, 2023 | Architects, Architecture

Sorry to hear of Doug Kelbaugh’s passing. I met him at Seaside when he was involved in the New Urbanism movement, but I first heard of him in 1973, in connection with a solar house that he built for himself in Princeton. It made an impression because unlike most solar-heated houses of that period, which had sloping solar collectors and resembled wedges of cheese, the Kelbaugh House had real architectural qualities. The house was passively solar heated by means of a Trombe wall, named for its inventor, Félix Trombe (1906-85), a French engineer who was in charge of building a 1000 kW solar furnace in southern France. I was doing research on solar stills, and I heard Trombe speak at a UNESCO conference in Paris in the Seventies. The basic principle of his device was simple: a south-facing thick masonry wall painted black, an air gap, and a glazed wall. The sun warmed the masonry, which at night radiated heat to the interior of the house. No fans or pumps (hence the “passive” moniker), and no angled solar collector, just a masonry wall. There was a bit more to it, but that is the idea in a nutshell. Doug added glazed windows to the wall, which meant that, unlike a collector, view was not entirely blocked. Very elegant.

CLEARING IN THE DISTANCE REDUX

by elementor | Feb 16, 2023 | Landscape architecture

Gakugei-Shuppansha has published a Japanese edition of A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the Nineteenth Century. This is the first foreign edition of the book, which was published by Scribner in 1999. Thanks to Mr. Hiroki Hiramatsu for spearheading this project and for his thoughtful translation. A social entrepreneur, Hiamatsu is the founder and CEO of Woonerf Inc. and co-founder of Green Building Japan.

AT THE BARNES

by elementor | Jan 27, 2023 | Architecture

In April 2005 I wrote my Slate column about the projected move of the Barnes Foundation to downtown Philadelphia: “Why not treat the galleries of the Barnes as an artistically significant artifact, and simply move them to the new location, burlap-covered walls and all? The result would resemble the transplanted historical interiors exhibited in many large museums, such as the Ottoman room at the Metropolitan Museum.” Well, that’s what they did—sort of. I had avoided visiting the new Barnes since I was attached to the original, but last week I finally relented. The collection hung as before (following a judge’s ruling), but thanks to Williams & Tsien’s tinkering, the feeling of the place had changed. Although the room layout was more or less the same, moldings had disappeared or been altered, and a kind of fussy modernist slickness permeated Paul Cret’s architecture. The collection itself can be a little overwhelming, and I was drawn—as I have been before—to Toulouse-Lautrec’s “A Montrouge.” After all those chubby Renoir nudes it is a breath of fresh air.

STACKED

by elementor | Dec 16, 2022 | Architecture

Duo Dickinson seems to have discovered the stacked box fad in a recent post on Common\Edge. Well, duh. In April 2009 I wrote a Slate column about “The Jenga Effect.” It was prompted by 56 Leonard Street, a New York apartment building designed by Herzog & De Meuron. Of course, what looked like a pile of stacked boxes was actually a conventional high-rise with cantilevers and setbacks. I think what attracted architects to stacking was the appearance of shakiness; architects in the past had always aimed at solidity, so why not go the other way? The granddaddy of stacked buildings was Habitat 67, but as I pointed out, Moshe Safdie’s stacked boxes were real boxes (of prefabricated concrete), and the stacking had a functional and structural logic. “While the rather loose arrangement appears random, it maximizes views from within the houses and provides one or more garden terraces for each unit. And the pyramidal stack looks very solid.”

FRESHENING UP THE PAST

by elementor | Dec 4, 2022 | Architecture

The Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery is an example of postmodernism, a style that was already in decline when Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown won a controversial competition to build this addition. In the eyes of many, including this writer, the Sainsbury Wing, like James Stirling’s Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, is one of the (rare?) paragons of postmodernism. So it was with dismay that I read the headline in Dezeen: “Sainsbury Wing Revamp Approved.” Revamp? Although the Sainsbury Wing is a Grade I-listed building, it apparently needs freshening up. The freshening up includes removing some of the non-structural columns in the lobby as well as carving a large Trump-like sign into the Portland stone facade. The chief motivation for the alterations is the dubious decision to convert the Sainsbury Wing into the main entrance to the Gallery. The lobby rendering released by Selldorf Architects shows a rather banal space that reminds me of an airport lounge, with none of the quirky brilliance that characterized the Venturi Scott Brown design. The British architecture critic Hugh Pearman told Dezeen that the proposed alterations “would be damagingly destructive—sterilizing the original architectural character of the building.” What a shame.

FOREIGN SHORES

by elementor | Nov 19, 2022 | Modern life

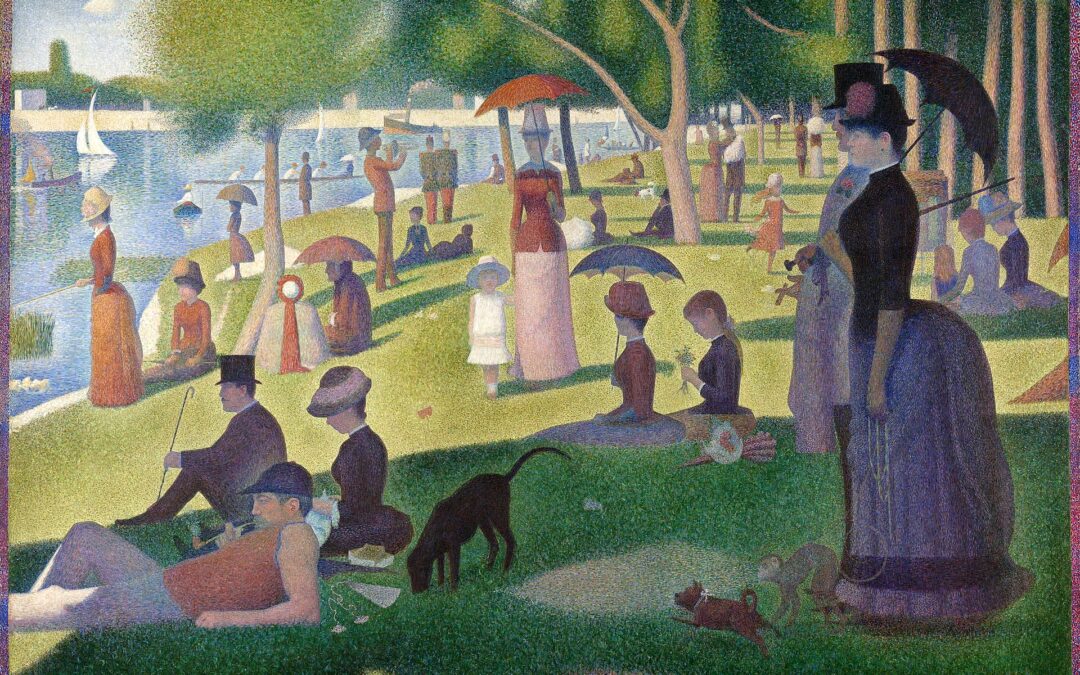

The Zhejiang University Press of Hangzhou has published Chinese translations of Home and Waiting for the Weekend. A reader of the latter will find a postcard with an image of Georges Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte,” which is referred to in the book and was on the jacket of the Viking edition, back in 1991. Nice. Zhejiang has also published a translation of One Good Turn, which is a natural history of the screwdriver and the screw. It’s printed on black paper–a first for me–and has a screw post binding. Like a shop manual!

CHARLESTON RENAISSANCE MAN

by elementor | Nov 9, 2022 | Architects

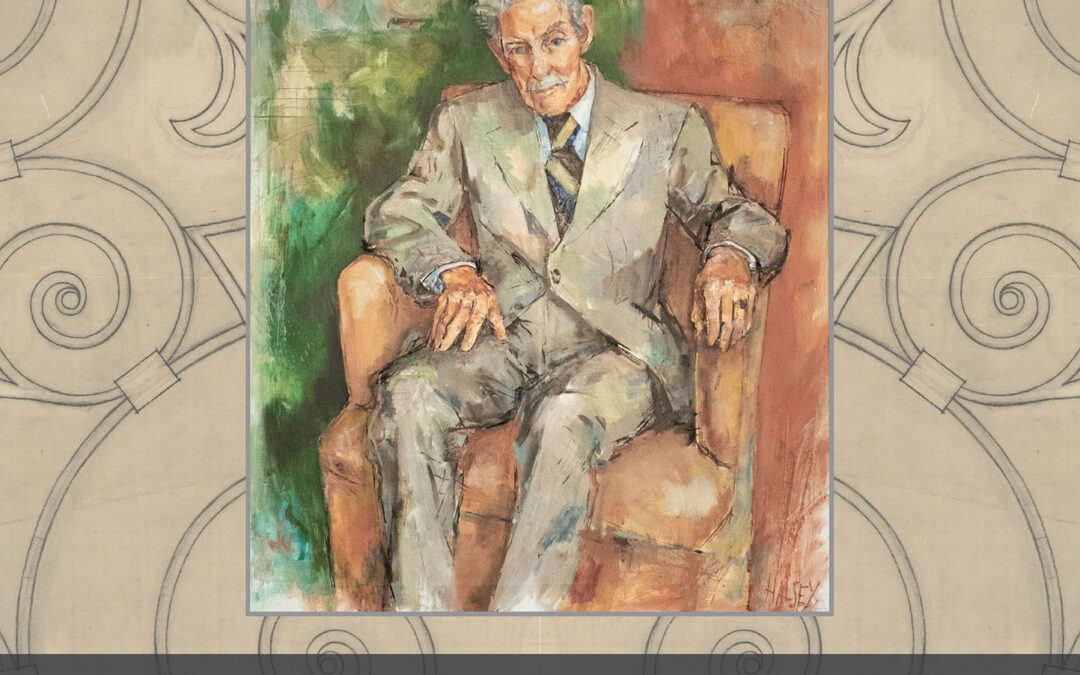

My friend Ralph Muldrow has just published a book on the life and work of Albert Simons (1890-1980), an architect of Charleston, South Carolina. Simons (rhymes with persimmons) is an interesting figure. Trained as a classicist he practiced during the period when architectural modernism was emerging and gaining predominance. He was also a leading figure in the Charleston architectural preservation movement, which means he was a leading figure nationally, for in 1931, Charleston passed an ordinance creating a historic district—the first American city to do so. You can read my Foreword here.

JACK DIAMOND

by elementor | Nov 6, 2022 | Architects

The architect Jack Diamond (1932-2022) died last week. He was perhaps Canada’s leading architect. Yet no-one would refer to him as a starchitect. “It’s easy to do an iconic building,” he once said, “because it’s only solving one issue.” Diamond’s designs were never one-dimensional. His opera house in Toronto is a traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium situated within an unprepossessing blue-black brick box whose chief feature is a glazed lobby facing one of the city’s main streets; dramatic, but hardly iconic—very Canadian. At $150 million in 2008, the cost of the Four Seasons Centre was modest as opera houses go, but more important was how the money was spent—on the hall and the interiors rather than on exterior architectural effects. Sadly Diamond would not be attending the gala reopening of his last project, the redone David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center. The New York Times’ Michael Kimmelman, writing about the architecture of the hall, was rather mealy-mouthed in his back-handed compliment, “it is like the second-best-looking man in an old Hollywood film: generic, attractive enough, ceding center stage to the star, which is the music.” But ceding center stage to the music is the whole point, isn’t it?

SHEDS

by elementor | Oct 30, 2022 | Architecture

Architecture mags these days cover a variety of topics—sustainable building materials, energy conservation, social equity; it seems that they have decided that building rather than architecture is their domain. But building and architecture are not the same. Nikolaus Pevsner’s introduction to his 1945 classic Outline of European Architecture began with this statement: “A bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture.” In my beat-up paperback copy, purchased when I was a student, I underlined the sentence and pencilled a question mark in the margin. In those halcyon days I had a youthful reaction to Pevsner’s provocation; now I’m not so sure he was wrong. Pevsner said that what distinguished architecture was its goal of aesthetic appeal. After spending four years writing The Story of Architecture I would expand that claim. The ambition of architecture is not only beauty but also the desire to celebrate, honor, pay homage, and often to impress. That, and not size or cost or function, is what sets architecture apart from building. When Victor Louis was designing the Palais-Royale speculative mixed-use project in Paris in 1781, he gave it similar architectural qualities as his earlier Grand Théâtre de Bordeaux. Both were works of architecture. Most of the newish apartment blocks that I see from my window are not—they are works of engineering and real estate development. I think that is what Frank Gehry was getting at by his controversial comment during a 2014 Spanish press conference: “Let me tell you one thing. In this world we are living in, 98 percent of everything that is built and designed today is pure shit. There’s no sense of design, no respect for humanity or for anything else. They are damn buildings and that’s it.”

THE LATEST