SLOW AND STEADY WINS THE DAY

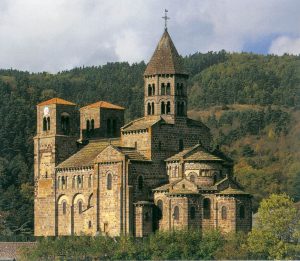

There is a long tradition of architectural research in structures—one thinks of Nervi, Candela, Torroja, and Frei Otto, the pioneers of concrete like Perret, and much earlier the Byzantine and Gothic builders. Architects have sometimes experimented successfully with new building techniques and materials (Rudolph invented striated concrete blocks; Foster was the first to use structural glass fins). But research into how people use buildings is rare. The profession has always recognized the value of so-called post-occupancy evaluation, and the need for knowledge based on how people actually behave in and use buildings. The problem has been that this kind of research is extremely complicated,

There is a long tradition of architectural research in structures—one thinks of Nervi, Candela, Torroja, and Frei Otto, the pioneers of concrete like Perret, and much earlier the Byzantine and Gothic builders. Architects have sometimes experimented successfully with new building techniques and materials (Rudolph invented striated concrete blocks; Foster was the first to use structural glass fins). But research into how people use buildings is rare. The profession has always recognized the value of so-called post-occupancy evaluation, and the need for knowledge based on how people actually behave in and use buildings. The problem has been that this kind of research is extremely complicated,

Is every building made out of concrete automatically Brutalist? The answer is yes, according to a recent

Is every building made out of concrete automatically Brutalist? The answer is yes, according to a recent  Norman Foster is building an office building in downtown Philadelphia. The Comcast Innovation and Technology Center, a 1,121-foot skyscraper, will be the tallest building in the city. Passing by the other day, I noticed elevator cabs scuttling up and down the side of the building. They reminded me of the external elevators on the Pompidou Center in Paris. Typical High Tech detail, I thought to myself, before I realized that these were construction elevators. The actual core is deep inside the building in the conventional fashion. And unlike Foster’s Hongkong & Shanghai Bank building, the structure is concealed as well (except for a vestigial expression of cross bracing on the otherwise pristine glass facade).

Norman Foster is building an office building in downtown Philadelphia. The Comcast Innovation and Technology Center, a 1,121-foot skyscraper, will be the tallest building in the city. Passing by the other day, I noticed elevator cabs scuttling up and down the side of the building. They reminded me of the external elevators on the Pompidou Center in Paris. Typical High Tech detail, I thought to myself, before I realized that these were construction elevators. The actual core is deep inside the building in the conventional fashion. And unlike Foster’s Hongkong & Shanghai Bank building, the structure is concealed as well (except for a vestigial expression of cross bracing on the otherwise pristine glass facade). These days, urban buildings are playing just one penny-whistle tune: glass, glass, glass. It’s as if there were a material shortage and we had run out of everything else. I don’t miss exposed concrete, but what about limestone and brick, terra cotta and granite? But no, architecture has been reduced to one material—even spandrels and soffits are glass. What explains this phenomenon? Well, of course it’s cheap. The engineer figures out the structure, and the architect wraps it in a glass skin. And the helpful glass manufacturers work out the details for you. It’s also easier to design. No more worrying about junctions between materials,

These days, urban buildings are playing just one penny-whistle tune: glass, glass, glass. It’s as if there were a material shortage and we had run out of everything else. I don’t miss exposed concrete, but what about limestone and brick, terra cotta and granite? But no, architecture has been reduced to one material—even spandrels and soffits are glass. What explains this phenomenon? Well, of course it’s cheap. The engineer figures out the structure, and the architect wraps it in a glass skin. And the helpful glass manufacturers work out the details for you. It’s also easier to design. No more worrying about junctions between materials, I went to see the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C. The building isn’t open to the public yet so I could only see the exterior. Yet because of its location on the National Mall this is one building whose exterior appearance is key. It’s the last structure on the north side of the Mall, down the hill from the Washington Monument. From a distance, the museum has a nice scale and an evocative form. The corona shape has always seemed symbolically right to me, recalling both traditional Yoruba tribal art and a Brancusi sculpture.

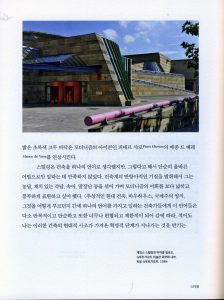

I went to see the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C. The building isn’t open to the public yet so I could only see the exterior. Yet because of its location on the National Mall this is one building whose exterior appearance is key. It’s the last structure on the north side of the Mall, down the hill from the Washington Monument. From a distance, the museum has a nice scale and an evocative form. The corona shape has always seemed symbolically right to me, recalling both traditional Yoruba tribal art and a Brancusi sculpture. One reviewer of How Architecture Works suggested that readers should have a iPad handy when they read my book so that they could refer to images of the buildings that are mentioned in the text. The book has photos, but they are black and white, and not large, the usual format for a trade book. Now the publisher Mimesis has solved that problem. The Korean edition of the book is illustrated with beautiful color photographs, many taking a full page, and in some cases (Salk Institute, Centre Pompidou, Bilbao Guggenheim) a two-page spread. Mimesis is the art-book arm of Open Books,

One reviewer of How Architecture Works suggested that readers should have a iPad handy when they read my book so that they could refer to images of the buildings that are mentioned in the text. The book has photos, but they are black and white, and not large, the usual format for a trade book. Now the publisher Mimesis has solved that problem. The Korean edition of the book is illustrated with beautiful color photographs, many taking a full page, and in some cases (Salk Institute, Centre Pompidou, Bilbao Guggenheim) a two-page spread. Mimesis is the art-book arm of Open Books, I recently watched an interesting

I recently watched an interesting