Plus ca change

The British architect for this amazingly insensitive addition is called Bureau de Change. Need one say more?

On Culture and Architecture

The British architect for this amazingly insensitive addition is called Bureau de Change. Need one say more?

A recent documentary film on the Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953), Incessant Visions, is a reminder of how history has treated the great architect: not well. He is best rememberd today for the idiosyncratic Einstein Tower in Potsdam, and for a series of expressionistic sketches that he drew while a soldier on the Russian front during the First World War. Yet he was by far the most productive—and the most technologically inventive—of the early modern pioneers (he was born the same year as Le Corbusier), building houses, department stores, synagogues, factories, and a cinema.

The United States has had a poet laureate since 1937. Why don’t we have an architect laureate? An architect laureate could be responsible for advising on important national monuments and memorials, or on makeovers of the Oval Office. The U.S. poet laureate is appointed by Congress, so an architect laureate might have advised congress to be a little more restrained in the $621 million Capitol Visitor Center, or perhaps referee the Eisenhower Memorial imbroglio. But I doubt Congress would look favorably on such a position. After all, building buildings costs money, poets are cheaper (currently $35,000 a year).

I attended a public lecture by my friend Enrique Norten last night. He described recent work: a museum in Puebla, a business school for Rutgers, and a city hall in Acapulco—all three competition winners, and all three under construction. All are impressive buildings in different ways. The museum is an addition shoe-horned into a historic complex of buildings, the university building is a self-conscious icon for a re-planned campus, and the capitol is an imaginative exercise in energy conservation. But what struck me is what he did not talk about, but which seemed to me an important aspect of his work: his Taste.

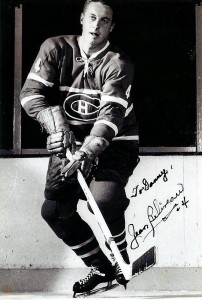

I was in Montreal recently and read in the local paper about the first Canadiens hockey game of the season, which was opened by Jean Beliveau (now 82). In his playing days, Beliveau was known as “Le Gros Bill,” after a popular 1949 French Canadian movie of the same name. Many top hockey players had nicknames: Maurice “Rocket” Richard, Bernard “Boom Boom” Geoffrion, Emile “Butch” Bouchard. The great Jacques Plante was “Jake the Snake.” Nicknames used to be popular. Actors had them, especially the old Western stars—George “Gabby” Hayes, Allan “Rocky” Lane, Alfred “Lash” LaRue, Edmund “Hoot” Gibson,

Architectural education differs from other creative fields: art students paint, ceramics students throw pots, film students film, but architecture students can’t build, they can only design. Nevertheless, ever since the Ecole des Beaux-Arts instituted the atelier system, the design studio has dominated architectural teaching. Never mind that this simulation of practice is actually very limited: there is no client, sometimes not even a site, programs are simplified, cost is rarely discussed, and construction is accorded a back seat. Moreover, design juries are generally composed exclusively of architects, rarely are engineers, developers, or lay people included. Little wonder that architects become accustomed to treating design as if it could be isolated from the outside world.

An architect friend reminded me of an extraordinary octagonal house in Natchez, Mississippi. Longwood was built just before the Civil War for Dr. Haller Nutt, a cotton planter, by the Philadelphia architect, Samuel Sloan. Construction was interrupted by the war (the Philadelphia craftsmen simply went home), and after Nutt’s death in 1864 construction stopped altogether. Although the brick shell and verandas were completed, only the basement was ever finished inside. Sloan’s plan is remarkable, since by the judicious placement of the verandas he manages to create two ranges of rooms (there were to be 32 rooms in all).

An article in today’s New York Times on classroom chairs reminded me of my schooldays. As far as I remember, we had wooden desks with a built in bench seats, attached to the floor. The desk-top, usually carved with a chronicle of interesting graffiti, was sometimes hinged with a storage space beneath that we never used. We didn’t used the hole in the top, which was made to hold an ink-well, either. The desks were sturdy and not particularly comfortable—they weren’t intended to be. The Times piece is full of fluff about how different classroom chairs might improve learning,