NOT THE POST OFFICE

by Witold | Feb 4, 2022 | Architecture

One of the stated goals of the American Institute of Architects Strategic Plan 2021-2025 is “To ensure equity in the profession.” Equity may apply to pay, work opportunities, awards, or even, I suppose, to the makeup of the profession, that is, it should reflect the population as a whole. But the architectural profession is not the post office. It depends on the availability and preferences of clients, it depends on the swings of the economy, and success relies on individual drive and talent. Architecture is a zero-sum game, of course: there are a limited number of building commissions at any one time and if one architect gets the job, another doesn’t. Some of the most prominent commissions—the ones that build a reputation—are the result of architectural competitions. In these blind auditions, only the most talented have a chance to shine. And talent is not evenly distributed; “cream rises” as Stewart Brand memorably wrote in the Whole Earth Catalog. Hard to put your thumb on that scale. Finally, opening up architecture implies increasing the size of the profession. But there are already too many architects! When I was a student in Canada in the 1960s, there were 6 schools of architecture—I know because on a federally-funded scholarship tour six of us fitted into a large station wagon. Today there are 12 schools. The US, with nine times the population, has not 108 but 140 NAAB-accredited schools.

LET’S PRETEND

by Witold | Jan 15, 2022 | Architecture

I’ve been watching a building going up a block from where I live in Philadelphia. 222 Market Street is a nineteen-story office block. The structure is steel, and except for a couple of odd slanted columns at one end, it is the sort of regular frame of I-beams that engineers have been designing for well over a hundred years; the first steel framed building in the U.S., was Burnham & Root’s ten-story Rand McNally Building in Chicago, erected in 1890. When the Market Street steel was topped off the structure reminded me of the high-rises that Mies van der Rohe put up in Chicago in the 1950s. Mies followed the age-old practice—going back to the ancient Greeks—of expressing the structure in the architecture; in his case in a very bare-bones fashion. That isn’t good enough for the architects of 222 Market (the global firm Gensler), whose approach I can only characterize as Let’s Pretend. The skin of the building, a combination of glass and flimsy-looking prefab glazed brick panels, is designed to give the impression that the building is composed of three-story high stacked-up boxes. In other words, architecture has been replaced by packaging.

THE TROPIC OF GRIEF

by Witold | Dec 30, 2021 | Modern life

Shortly after my wife died, a friend emailed me a quote from Julian Barnes’s Levels of Life, which deals in part with the death of his wife of twenty-nine years. “This is what those who haven’t crossed the tropic of grief often fail to understand,” Barnes wrote, “the fact that someone has died may mean that they are not alive, but doesn’t mean that they do not exist.” It struck me as an intellectual conceit rather than a real insight. But I ordered the book from Abebooks. It was well written, as I had expected, and it was full of aperçus such as: “There are two essential types of loneliness: that of not having found someone to love, and that of having been deprived of the one you did love. The first is worse.” But I was still unconvinced that someone who had died could nevertheless exist. No longer. For me, Shirley does exist, not the memory of her, but her actual presence in our home—and in my consciousness. “I talk to her constantly,” was another Barnes comment that struck me as farfetched when I first read it. Now, months later, I must agree, for I, too, talk to her constantly.

FAME

by Witold | Dec 24, 2021 | Architects, Architecture

I’ve just finished reading Roxanne Williamson’s American Architects and the Mechanics of Fame (1991). Despite some interesting historical research into the professional connections between architects and their mentors/employers, it is not a very satisfying book. The first question to ask about fame is “Who is judging?” The public, the architectural profession, the critics, architectural historians? Williamson considered only the last group. She compiled an “Index of Fame” by consulting twenty histories of architecture and four encyclopedias, and counting the number of times individual architects were listed. Since most recent historians (Giedion, Hitchcock, Banham, Pevsner, Fitch, and Scully) were interested in the history of modernism, this naturally skewed the results. An architect such as Rudolph Schindler, who designed a handful of interesting private houses was more “famous” than Paul Philippe Cret, who built major civic buildings such as the Federal Reserve, the Detroit Institute of Art, the Walter Reed Hospital, and much of the campus of the University of Texas in Austin. The second problem is that she treats fame as an absolute quality. But, as the old saying goes, “All glory is fleeting.” Sixty years ago, when I was a student, the architects we admired were Aldo Van Eyck, Peter and Allison Smithson, and Shadrach Woods, long since forgotten (none appear in Williamson’s book). But neither does the “Index of Fame” include Norman Foster, who, in the years since the research for this book was conducted (the late 1970s) has become the world’s most recognized architect (and the richest). If you are going to study fame—a dubious undertaking, in any case—you must incorporate a sliding time scale: famous today, not so famous tomorrow, and vice versa.

M. ROGERS

by Witold | Dec 19, 2021 | Architects, Architecture

The architect Richard Rogers, 88, died yesterday. His obituaries invariably started by mentioning the Centre Pompidou, the seriously ill-conceived museum that turned the youthful Rogers and his partner Renzo Piano, into overnight sensations. I remember that when I was a member of the Commission of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C., a now seasoned Rogers came before us to present 300 New Jersey Avenue, an addition to an old office building near Union Station. The limestone building was designed in 1935 by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (the architects of the Empire State Building), a fine example of early American modernism: a blend of practical engineering, Beaux-Arts planning, and an Art Deco sensibility. When Rogers presented his concept—a ten-story glass wing that created a triangular atrium between the new and the old buildings—the sketchy drawings and a patchy model were hard to understand. Exactly where was the design heading? Over subsequent presentations, the project slowly jelled, but was still hard to follow. A few years later, my fellow commissioner, Michael McKinnell, and I went to see the built result. The jungle-gym aesthetic, structural struts, and brash colors, were world’s away from Shreve, Lamb & Harmon’s orderly design. “That was then, this is now,” seemed to be Rogers’s message. Contrasting the new with the old has become an architectural cliché that often leaves the old in its dust, but here we came away admiring both buildings. Both evinced a strong sense of conviction—a key architectural quality. Chapeau, M. Rogers!

RULES OF THUMB

by Witold | Dec 8, 2021 | Architecture

At a time when most schools of architecture have courses in what is referred to as “history-theory,” I was struck by a sentence in Laurie Olin’s forthcoming collection, Essays on Landscape. “Contrary to many architects I knew, I believed that theory is developed in retrospect, to account for what had been or was being done in the field, and that it rarely preceded or led creative practice.” Just so. Some buildings are, in a sense, experiments, and when something works, and is taken up by others, it eventually becomes a rule of thumb, perhaps even a theory. Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language is full of rules of thumb: rooms are nicer when they have windows on at least two sides; vary ceiling heights; a staircase can be a stage. Such rules develop from observation, which is why architectural training has traditionally included travel—it’s important to see things for yourself, and especially to see those seminal buildings that have given rise to rules of thumb—Bramante’s Tempietto, Schinkel’s Altesmuseum, Gehry’s Bilbao. Architecture resembles engineering in that practice leads theory, not vice versa. First you build a flying machine, and later you discover the aerodynamic theory that supports flight.

Photo: Caspar David Friedrich, Woman at a Window, 1822

GOING ON

by Witold | Nov 20, 2021 | Modern life

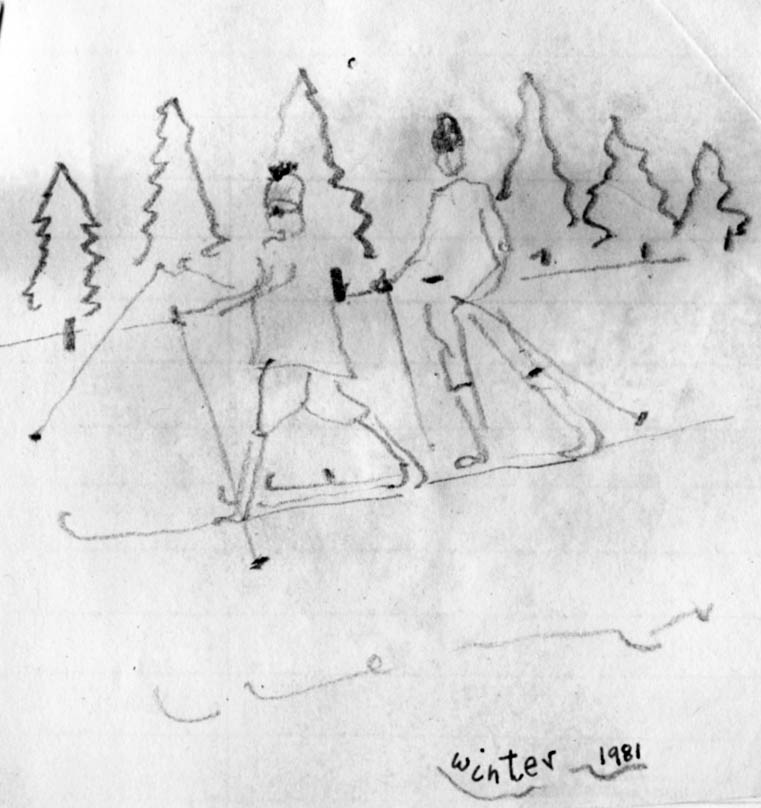

Years ago, when Shirley and I lived in Quebec, we regularly took a few days off during the winter to stay at a country inn in the Laurentians, north of Montreal. It was run by a German family, and the hearty food—schnitzel and kartoffelklöße—was a big part of the attraction. So was the cross-country skiing. We could ski out of the front door of our house in Hemmingford, but it was quite flat so hilly terrain was more fun. The trails were long and the area was quite wild. One day we went out, and after several hours I had to admit that we were quite lost. It was the end of the afternoon and getting cold. We soldiered on. At one point I felt very tired and just wanted to lie down and rest. Just for a short time, I said. Shirley would have none of it. She scolded me, and made me get up. We finally made it back to the inn at nightfall; I think they were about to send out a search party.

That’s what she would tell me today. “Now, go on.”

MEMORIES

by Witold | Nov 9, 2021 | Architecture

Last week I visited Planting Fields, a Jazz Age estate on Long Island’s Gold Coast. The house was completed in 1921, designed by Alexander Stewart Walker (1876–1952) and Leon Narcisse Gillette (1878–1945), whose Manhattan firm was responsible for several Long Island country houses. The style of the house is usually described as Tudor Revival. Walking around the sprawling mansion I was reminded why historical revival styles were so popular for so long. To begin with, the house is not really a recreation of a particular historical period. There are half-timbered parts, limestone parts, and an entry that reminded me of Christopher Wren. This picturesque variety achieves several goals. It breaks down the scale. A 67-room house risks feeling like a small hotel, and chopping it up into bite-sized portions preserves a domestic atmosphere that while hardly cosy, is certainly comfortable. It also allows architectural variety on the interior, which includes a Norman entry hall, medieval gallery, a French Rococo reception room, a lighthearted bedroom designed by Elsie de Wolfe, and a breakfast room with a buffalo themed mural by Robert Winthrop Chanler that defies easy stylistic categorization. It is a common mistake to think of revival styles as a reproduction of something. Instead, they are more like a rough framework for memories, real and imagined In the case of Planting Fields, the framework resonated with the owners. William Coe was born in England (he arrived with his parents when he was ten, and worked his way up from office boy in an insurance office to president of the firm). His wife Mai, a wealthy heiress (daughter of Standard Oil founder, Henry “Hell Hound” Rogers) also had a British connection—the house was inspired by the English Tudor manor house that belonged to her sister. We live in an age when architectural conformity—and consistency—is the rule, and when looking backward is considered retardataire. More’s the pity.

JUST A SERVICE ENTRANCE

by Witold | Oct 29, 2021 | Architecture

I think it was Christopher Alexander who I once heard observe that everything in our surroundings—everything—either raises our spirits or dampens them. It may only be a notch or two, but every thing we look at makes us feel either slightly better or slightly worse. My afternoon walk often takes me past the rear of the Board of Education Building in Philadelphia, and a detail in that building always gives me a lift. It’s the service entrance. I know that’s what it is because the name is elegantly carved into the stone door frame. The building was designed in 1930 in a style sometimes called Moderne, a fusion of Classicism with Art Deco, and the pediment above the doorway reflects this aesthetic. Is there any doubt that a service entrance designed in 2021 would be very different? The pioneers of modernism, who would scoff at the ornamental bracket and the paneled and studded door, bear a heavy responsibility. Not only did they put blinders on designers so that the past became forbidden—and forgotten—territory. They provided permission to mediocre talents to produce and even celebrate mediocrity. The designer of the service entrance that I admire, Irwin Thornton Catharine (1884-1944), was not a celebrated architect; he didn’t attend the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, or even a university (he had a Certificate in Architecture from the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry). But he had a long and deep tradition to draw on, and a toolbox of design skills to deploy. He produced not a utilitarian door surrounded by a skimpy frame, but something solid and weighty, something beautiful, something to raise the spirits. Thank you Irwin.

A PAST WORTH SAVING

by Witold | Oct 17, 2021 | Architecture

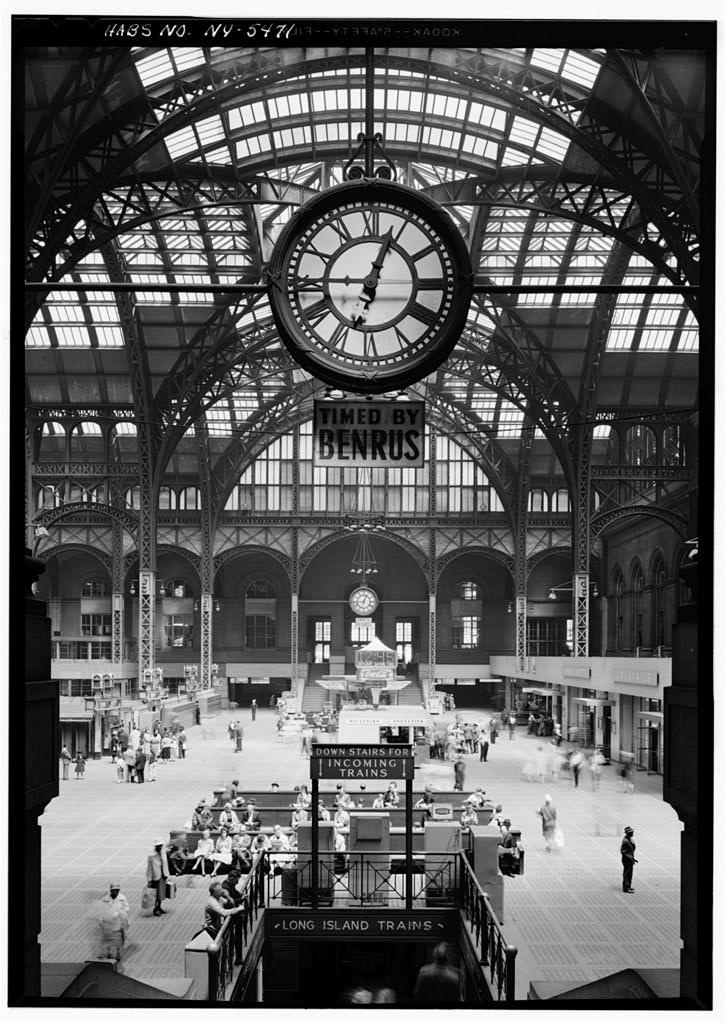

The historic preservation movement, as I think Vincent Scully once pointed out, was the most powerful expression of public interest in architecture of the twentieth century. But the truth is that the historic preservation movement was not really about preserving the past; people did not want to save Penn Station because it was old, or because it was an expression of a particular era. They wanted to save it because it was beautiful, beautifully conceived and beautifully built. The four decades between 1900 and 1940 were a magical period in American architecture. Comparable, as Augustus Saint-Gaudens observed, to the Italian Renaissance—a perfect joining of money, patronage, taste, and skills. As Charles McKim showed at Penn Station, you could solve a modern problem like a railroad station without renouncing the past, indeed, that past made the modern solution all the more convincing.

THE LATEST