THE END OF ARCHITECTURE?

by elementor | Mar 29, 2024 | Architecture

I got an email request the other day. The sender had asked ChatGPT “What are the best articles about architecture written since 1990?” and the third recommendation, after two essays by Koolhaas, was “The End of Architecture?” by Witold Rybczynski. According to the bot, “In this provocative article published in 1996, Rybczynski reflects on the state of architecture at the end of the 20th century and questions whether the discipline has reached its limits or if new directions are emerging.” Stirring stuff. Could I send a link to the article, my correspondent asked? He had been unable to find it online, he explained.

No wonder he had trouble finding it—this article doesn’t exist. I never wrote “The End of Architecture?” but perhaps I should have. When I look at the new buildings going up in my neighborhood, the results don’t really qualify as Architecture. In a chapter titled “The Fundamental Principles of Architecture,” Vitruvius wrote: “Architecture depends on Order, Arrangement, Eurythmy [beauty], Symmetry, Propriety, and Economy.” I search in vain for these qualities. By economy, Vitruvius did not mean cheapness—there’s plenty of that—but rather suitability, that is, how a building is appropriate to its station in life. I look in vain for a sense of private decorum in a row of chic houses, or a sense of public sobriety in a whimsical legal office building. Was ChatGPT just “halucinating,” or was it sending a message?

ORDER WITHOUT DESIGN

by elementor | Mar 12, 2024 | Urbanism

Last summer I ran into Alain Bertaud in Charleston (above). We had first met in India, when he was at the World Bank and I was at McGill Uiversity, working on a research project with B.V. Doshi’s Vastu Shilpa Foundation. I had not seen Alain in the intervening forty years yet our conversation effortlessly picked up where it left off. We were both architects who had been drawn to urbanism, which is not that unusual, but we also shared the rarer experience of being exposed to urban economists, and learning to see city planning through their eyes. Alain describes his experience in Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities (MIT Press, 2018). This book is based on the simple thesis that “cities are primarily labor markets,” and in that sense it is as mighty a critique of city planning as Jane Jacobs’s Life and Death of Great American Cities was fifty-five years ago. Like Jacobs, Bertaud observes rather than theorizes, except that he casts his eye far and wide, on cities in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Bertaud brings more than five decades of experience to the task. Ed Glaeser has called him “one of the world’s great urbanists.” No exaggeration.

RADOSLAV ZUK (1931-2024)

by elementor | Feb 27, 2024 | Architects

Rad Zuk was a longtime colleague of mine when I taught at McGill for two decades, but my first encounter with him was when I was a student there in the 1960s. I was in the penultimate year of a six-year course. Zuk had joined the faculty a year or two earlier, and I had not had him as a teacher, but somehow I ended up briefly working for him. I can’t remember if he approached me, or if I saw a want ad on the school bulletin board. The job was to draw up a project he was working on—a church. I didn’t know then that he specialized in Ukrainian Greek Catholic churches, having already built several in Manitoba, where he had been living. He was an ethnic Ukrainian, born in Lubaczów, Poland, grew up in Austria, and emigrated to Canada, studying architecture at McGill and MIT. I wasn’t sure what to make of his project. Like Orthodox churches, Ukrainian Greek Catholic churches have specific architectural traditions, onion domes, icons, painted interiors. Zuk’s design had these features, but it also had a modern plan that was rigorously Miesian. This was a blending of new and old, but with none of the tongue-in-cheek mimicry which would characterize the postmodernism movement that would appear in a few years. Zuk was always serious about design, although in his characteristically low-key and gentle way. His last project was the Nativity of the Theotokos Chuch in Lviv (see above). New and old, indeed.

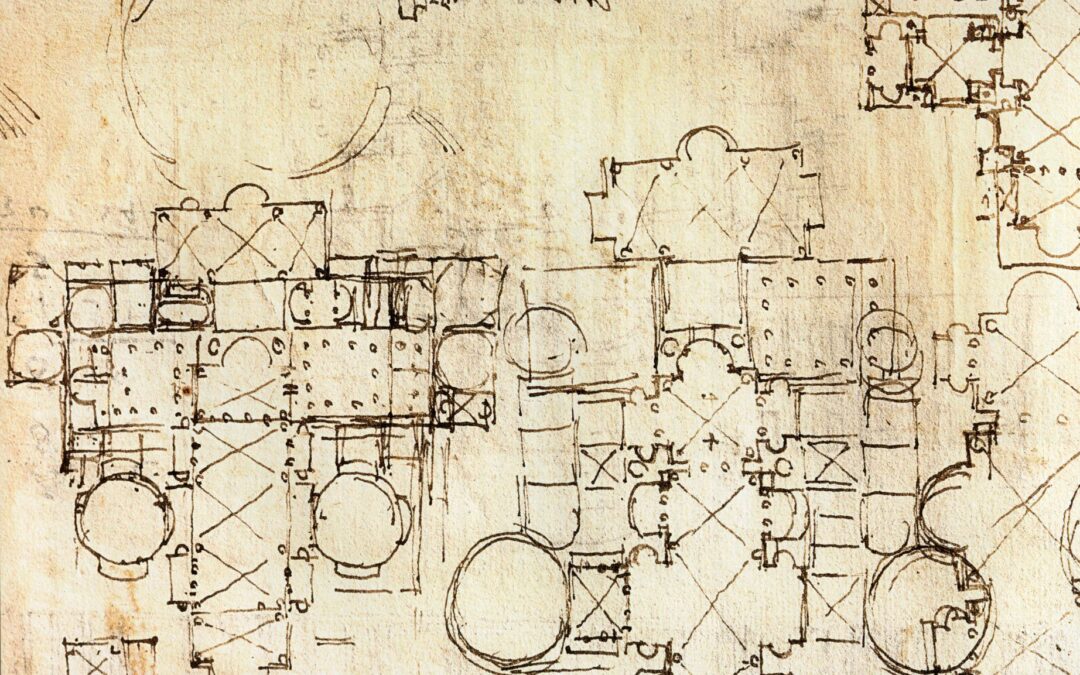

MAKE A GLASS

by elementor | Feb 25, 2024 | Architecture, Design

In the past, when a “master” was recognized he usually became an influence (Bramante, Palladio, and Michelangelo or, Oud, Corbusier and Mies). Today, while we recognize masters, we seem unable—on unwilling—to learn from them.

Or maybe it is a misplaced emphasis on originality. I still remember my very first design assignment in school. I admired Marcel Breuer’s houses, so my first stab at design was an imitation. I was told in no uncertain terms that this was not the correct way to proceed. I thought of this the other day when I was listening to an interview with Bret Stephens, the NYT columnist. Asked what advice he would give an aspiring opinion journalist, he said find someone you admire and copy them, try to figure out how they do it, and eventually you will develop your own style. I think that would have been much better advice to an architectural tyro than “dream up something new.”

Another related story. At one point in my life I spent a summer in Bavaria learning how to blow glass. Don’t ask me why. The first day I was seduced by the fluid, malleable molten material. My teacher, Erwin Eisch, a famous glass artist, told me: why don’t you just make an ordinary glass. That took me the rest of the day. I still have it, a misshapen awkward thing, but more or less a glass.

YOU CAN’T GO HOME AGAIN

by elementor | Feb 19, 2024 | Architecture

I’ve been writing about Planting Fields, a Roaring Twenties estate on Long Island’s North Shore, Great Gatsby territory. The house, an impressive Tudor pile, was designed by Walker & Gillette in 1918-22; the garden was laid out by Olmsted Brothers. Like the more than five hundred country retreats that were built on the so-called Gold Coast during that era, it was inspired by the British country house, think Brideshead or Downton Abbey. But while the American versions of manors, chateaux, and villas, are beautiful architecturally, they are hollow representations of an unattainable ideal. These country family seats lasted less than one generation before their sprawling grounds were subdivided and sold off, the houses themselves either demolished or converted into institutional or commercial uses. In that regard Planting Fields is unusual. Its 400 acres survive as a state historic park and arboretum. It’s now been a public place longer than it ever was a private home. The house is there, too, a touching relic of a makebelieve moment.

THE WISDOM OF EXPERIENCE

by elementor | Jan 30, 2024 | Architecture

I was recently listening to an online interview with Bret Stephens. Speaking admiringly of the nineteenth-century Anglo-Irish political philosopher Edmund Burke, the New York Times columnist referred to Burke’s approach as “the wisdom of experience rather than the wisdom of theory.” While this pithy observation describes liberal politics, it struck me that it could equally be applied to architecture. At its best, this is an art of the possible, that is, what has worked rather than what should work. That is why architects in the past generally studied a widely accepted canon—the accumulated wisdom of experience. It was only in the late twentieth century that “History Theory” emerged as an architectural discipline, a—misguided in my opinion—attempt to promote a wisdom of the other kind.

INHERITANCES

by elementor | Jan 13, 2024 | Architecture

A while back I wrote a blog on the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art’s indiscriminate use of “classical” and “traditional.” More recently I’ve been writing an essay about the origins of the American campus and the Collegiate Gothic style. I was reading the chapter on “Educational Groups” in The American Vitruvius, Werner Hegemann and Elbert Peets’s “Handbook of Civic Art,” published in 1922. It’s clear that at that time classicists did not consider Gothic to be an acceptable style. “Some recent designs for the grounds of colleges and similar institutions have abandoned both American tradition and the classic forms from which American tradition is derived and have elected Gothic and Elizabethan forms instead, which have no roots in the traditional art of this continent,” wrote the authors. Pointedly, they did not include prominent Collegiate Gothic buildings such as Cope & Stewardson’s Quadrangle at Penn (above), or Ralph Adams Cram’s Graduate College at Princeton.

Is classicism the only American tradition? I think one could make a good case that the Gothic is as much rooted in early American history. Examples include Trinity Church in New Haven (1812), Richard Upjohn’s Trinity Church in New York (1840), and James Renwick’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral (1859). Cram certainly considered Collegiate Gothic to be a part of America’s cultural heritage. Describing Penn’s Quadrangle buildings he wrote: “First of all, let it be said at once that primarily they are what they should be: scholastic in inspiration and effect, and scholastic of the type that is ours by inheritance, of Oxford and Cambridge, not of Padua or Wittenberg or Paris.” I suspect that in Cram’s mind, the inheritance of Anglo-Saxon culture trumped that of imperial Rome.

WITHOUT SHIRLEY

by elementor | Jan 9, 2024 | Modern life

It is the third year of my life without Shirley. The period of intense grief has passed, but with it also the immediacy of her absence. I still talk to her, and I still occasionally get the feeling that she will knock on my door, like a character in a Hollywood paranormal movie. I would tell her about what she’s missed: the time the Schuylkill breached its banks and our building got flooded; my visit two summers ago to Northeast Harbor in Maine, where we once spent a happy week; my last book, my next book. In truth, there is not much to relate. My life has slowed down, it is as if someone had lowered my setting to half speed.

UNSTICKING

by elementor | Dec 15, 2023 | Architecture

“What is to be done?” my friend asked. We had been discussing the rather low current state of architecture, countless glass boxes, undisciplined and arbitrary designs, a profession at sea. We have been here before. Because fashion is an unavoidable aspect of architecture—not the main thing, but always lurking in the background—architecture does not evolve steadily like science or technology, it swings back and forth and occasionally gets grounded. That happened in the United States in the late nineteenth century, and it took a Richardson and a McKim to shake it out of its lethargy. Something similar happened in the 1970s, after the International Style had worn itself out. James Stirling put it well when he said at the time “The language itself was so reductive that only exceptional people could design modern buildings in a way that was interesting. It got stuck and it will have to unstick itself to move one.” Stirling, along with Graves and Venturi, looked to the past to help with that unsticking, but the result—Postmodernism—proved thin gruel. Can digital computing provide a more substantive answer? Proponents trumpet the virtues of “parametric architecture,” but design technology (the pencil?) and constructional breakthroughs (reinforced concrete?) have rarely moved the architectural needle. So what does? A fortuitous confederacy of talents helps: Brunelleschi, Alberti, and Bramante in the Renaissance; McKim, Burnham, Saint-Gaudens and others in the American Renaissance; Corbusier, Mies, and Aalto in the early Modern Movement. This doesn’t always work: the emergence of gifted architects such as Rudolph, Kahn, and Van Eyck, in the 1960s proved insufficient. A necessary—though not sufficient—condition for creating architecture is wealth and stability, so disruptions to these can sometimes unstick worn-out thinking: the collapse of the Roman Empire, the rise of European city states, the First World War. Whatever the cause, unsticking architecture, when it occurs, is usually unforeseen, unplanned, and contingent. We shall have to wait and see, I told my friend. I’m not sure that he found that very helpful.

IRONY

by elementor | Dec 7, 2023 | Architects, Architecture

Describing the Königliches Schloss, the rebuilt imperial palace in Berlin, Michael J. Lewis wrote recently in The New Criterion: “It is not so much a recreation of the palace as a workmanlike scale model of the original, placed on the original site, and with something of the gift that Robert Venturi gave to historic preservation, which is a saving leaven of self-aware irony.” This is a useful insight: irony is a way for modernists to deal with the past without actually acknowledging its primacy. But was Venturi’s “leaven of self-aware irony” a gift or a poison pill? Venturi’s firm lost important commissions such as the Philadelphia concert hall precisely because clients did not appreciate ironic, or sometimes downright jokey, architectural asides. Most clients—Vanna Venturi aside—are loathe to see their money spent on something as insubstantial and potentially risible as irony. And irony gets stale over time; is that why so many VSB buildings have fared poorly, being insensitively enlarged, or demolished as in the recent case of the Abrams House (see above) in Pittsburgh? Absent idiosyncratic follies and amusement parks, architecture is more serious than that.

THE LATEST