THE WRECKER’S BALL

by Witold | Jun 7, 2021 | Architecture

The Architect’s Newspaper reports that two “historic Brutalist” buildings in Trenton, N.J. are in the process of being demolished. The early 1960s buildings, which housed offices and labs of the state government, are the work of Alfred and Jane West Clauss, both partners in Clauss & Nolan. The German-born Alfred Clauss (1906-98) worked briefly for Mies on the Barcelona Pavilion and after emigrating to the U.S. he worked for George Howe on the PSFS Building and was one of the Philadelphians whom Howe brought to teach at Yale (Louis Kahn was another). Jane Clauss (1907-2003), born in Minneapolis, worked for Le Corbusier in Paris and met her husband when both were designing wartime housing for the TVA. The Trenton buildings are a cube and a cylinder clad in precast concrete panels. It is not clear what makes them historic. The Antique Automobile Club of America defines an antique car as over 25 years of age, so in that sense perhaps they qualify, and I suppose that like any old building they represent a historical moment. In this case, it was the time when architects turned away from the reductive minimalism of the International Style and began to experiment with facades of modeled concrete. Not exactly Brutalism, this was an awkward blend that even a master like Marcel Breuer could not always pull off. This bland and unappealing architecture failed to capture the public’s affection, which may explain why these buildings frequently fall victim to the wrecker’s ball.

ART FOR ART’S SAKE

by Witold | Jun 6, 2021 | Architecture

Art Nouveau lasted only a few decades; it appeared around 1890 and came to an end shortly after the First World War. Perhaps for that reason, it is often given short shrift by art historians who see it as a not altogether respectable prelude to modernism. “With novelty [Art Nouveau] must most certainly be connected, and liberty at least in the sense of license is applicable too,” sniffed Nikolaus Pevsner, who called it “suspiciously sophisticated and refined.” He did not explain why sophistication and refinement were disqualifying qualities. “Art Nouveau is outré and directs its appeal to the aesthete, the one who is ready to accept the dangerous tenet of art for art’s sake.” Pevsner wrote that in 1936. Fashions may be transitory but buildings last a long time. Eighty-five years later, art for art’s sake remains widely popular—Hector Guimard’s 1900 Metro stations are a cherished part of the Parisian streetscape—whereas it is the early work of the International Style that is outré, appealing not to the public but to the aesthete. The truth is that architectural movements should not be judged by the duration of their ascendancy, but rather by the duration of their impact on society as a whole. By this measure such later short-lived flights of fancy as Art Deco and PWA Moderne likewise gain our respect. Brutalism and Postmodernism, not so much.

POMO

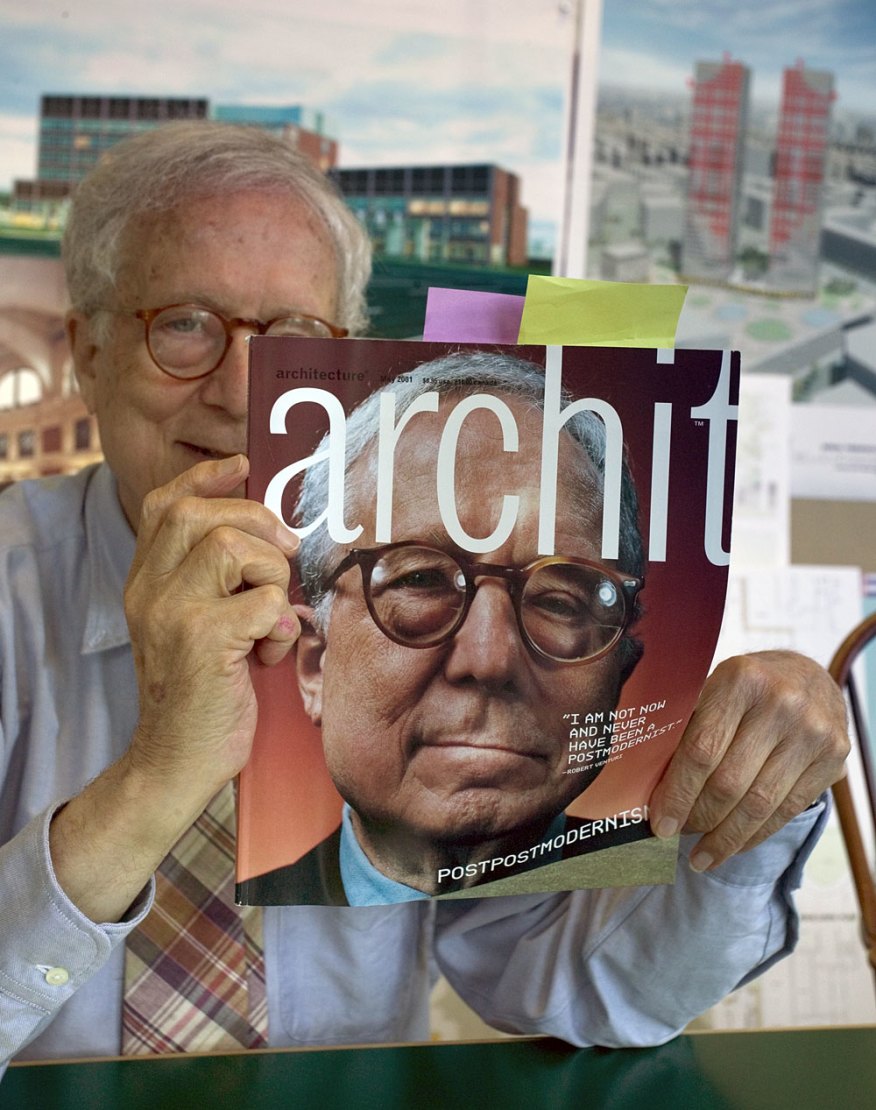

by Witold | Jun 5, 2021 | Architecture

“I am not now and never have been a postmodernist,” said Robert Venturi twenty years ago; the quote appeared on the cover of the May 2001 issue of Architecture. But of course he was a postmodernist, although it is no wonder that he wanted to disassociate himself from that movement; after several decades PoMo had run its course, moreover in hindsight it appeared that it had done more harm than good. The best postmodernists had produced first-rate work—the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, the Sainsbury Wing in London, the Beverly Hills Civic Center—but few architects were as historically knowledgable as James Stirling, Venturi, and Charles Moore—and in less capable hands PoMo was thin gruel indeed: an unconvincing blend of ersatz history and weak-kneed modernism. It’s easy to ridicule postmodernism today, but it is worth remembering what it was reacting against: lumbering Brutalism, warmed-over Mies, inept minimalism. Stirling was critical of modernist conventions: “The language itself was so reductive that only exceptional people could design modern buildings in a way that was interesting.” Postmodernism ultimately proved a failure as a broad-based movement—it turned out that only exceptional people could design interesting postmodern buildings, too. In that regard, it was much less successful than earlier short-lived architectural episodes such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

MAKE HISTORY

by Witold | Jun 4, 2021 | Architecture

Last night I listened to an ICAA Zoom lecture by the architect Tom Kligerman, whose firm—Ike, Kligerman, Barkley—specializes in beautifully crafted houses, which were the subject of his talk: “New Thoughts on the American Home.” While many of the designs could be described as traditional, others were distinctly modern, and some were an eclectic combination of the two. Evidently catholic in its taste, IKB was clearly not committed to a canonic approach to the classical past. Kligerman observed that in his opinion architects should aim to make history, not simply be inspired by it. This has surely been the motivation of all creative architects over the years, whether they were Palladio, Edwin Lutyens, or Bertram Goodhue. All combined their historical interest with other influences; Veneto traditions in villas, Moghul motifs in New Delhi, and Middle Eastern architecture in the Nebraska capitol. Not wedded to the past but using it as a springboard to move forward.

Photo: Modern Farmhouse, Princeton (IKB Architects)

DAN FRANK

by Witold | May 31, 2021 | Modern life

Dan Frank, 67, died last week. He was the editorial director of Pantheon Books, but when I knew him, in the late 1980s, he was a young editor at Viking Press working with me on The Most Beautiful House in the World and Waiting for the Weekend. This was still early days for me as a writer and I was lucky to have someone as patient yet demanding as Dan. And as supportive. After the success of Home and The Most Beautiful House in the World I might have specialized in domestic non-fiction, becoming a sort of literary Martha Stewart. Dan never pushed me in that direction, and when I proposed a book about the history of the weekend he was encouraging. When I dedicated my next book, an essay collection, to “My Editors,” I was thinking of Dan.

ORWELLIAN

by Witold | May 30, 2021 | Modern life

In a 1946 essay on politics and the English language, George Orwell criticized pretentious diction and meaningless words. “Adjectives like epoch-making, epic, historic, unforgettable, triumphant, age-old, inevitable, inexorable, veritable, are used to dignify the sordid process of international politics, while writing that aims at glorifying war usually takes on an archaic color, its characteristic words being: realm, throne, chariot, mailed fist, trident, sword, shield, buckler, banner, jackboot, clarion. Foreign words and expressions such as cul de sac, ancien regime, deus ex machina, mutatis mutandis, status quo, gleichschaltung, weltanschauung, are used to give an air of culture and elegance.” What would he have made of today’s slew of popular adjectives: social (distancing), societal (change), equitable (outcomes), or systemic (racism)? “A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks,” observed Orwell. “It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier to have foolish thoughts.”

THE COMMISSION

by Witold | May 27, 2021 | Architecture

President Biden’s decision to appoint four new members to the U.S Commission of Fine Arts has focussed public attention on this body. The New York Times rather snarkily described the Commission as a “low-key, earnest design advisory group”; just tell that to the architectural firms that have had to undergo detailed and sometimes severe reviews. Not all the reporting has been accurate; the Commission does not report to Congress, nor is the chair appointed, he or she is elected by the commissioners.

The Commission of Fine Arts was created in 1909 personally by President Theodore Roosevelt to act as an aesthetic watchdog over the urban makeover of Washington, D.C. that produced the National Mall, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Jefferson Memorial, as well as an extensive urban park system. Congress formalized Roosevelt’s decision a year later. The Commission reviews the designs of new federal buildings, monuments, and memorials in the District, as well as all new buildings—private as well as public—in the monumental core of the city. Over the years the Commission’s responsibilities have grown to include reviewing overseas military cemeteries, all coins and medals issued by the U.S. Mint, and heraldic designs of the Army. When Charles Freer founded the Freer Gallery he stipulated that all acquisitions (and deaccessions) be approved by the Commission, and when I was a member, one of our more pleasurable duties was to visit the Gallery and inspect their latest acquisitions.

There are seven members of the Commission, appointed by the President for four-year terms. The first commissioners included Daniel Burnham, Thomas Hastings (architect of the New York Public Library), Cass Gilbert (architect of the Supreme Court), the sculptor Daniel Chester French, and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. Such prominent architects as Charles A. Platt, John Russell Pope, Henry Bacon, and Paul Cret later served; so did the artists Lee Lawrie and Paul Manship. The postwar period saw such leading designers as Pietro Belluschi, Wallace K. Harrison, Hideo Sasaki, Gordon Bunshaft, and Kevin Roche. It also included leading figures in the design field such as Aline Saarinen and Adele Chatfield-Taylor. There have been periods when appointments to the Commission have been political, but generally it is composed of architects, landscape architects, and artists. J. Carter Brown, the director of the National Gallery, was chair for three decades, and was followed by his successor at the Gallery, Rusty Powell. Commissioners serve at the pleasure of the president, and President Biden was entirely within his rights to make replacement appointments, although this is the first time a president has done so. It is a shame that the National Gallery is no longer represented, and I hope a landscape architect will join the Commission in the not too distant future.

Photo: John Russell Pope’s proposal for the Lincoln Memorial, 1911-12

THE BEDPAN LINE

by Witold | May 26, 2021 | Modern life

I spent some time in a hospital room recently, visiting. The atmosphere was distinctly technological: screens, flashing lights, mechanical beds, not to mention numerous pharmaceuticals. I was brought up short by the appearance of a device that was more Florence Nightingale than Big Pharma: a bedpan. The bedpan was plastic, but I’d always thought of them as glazed metal. Early bedpans were made of ceramic and were heavy affairs. A famous bedpan, made of pewter, belonged to Martha and George Washington, but the device is much older than the Colonial period. The Science Museum in London has a collection of old British and French bedpans, ingenious designs in which the hollow handle doubles as a pouring spout. The oldest model, made of glazed earthenware, is vaguely dated “1501-1700.” The earlier date suggests that the origin of the bedpan might be medieval. That inventive period gave us the windmill, the printing press, and eyeglasses—and perhaps the bedpan. Apropos of nothing, I came across a humorous reference: the British suburban railway line linking the city of Bedford to London’s St Pancras station is nicknamed the Bedpan Line.

Photo:Bedpan, 1501-1700

PHILLY PHLASH

by Witold | May 11, 2021 | Architects, Architecture

Helmut Jahn (1940-2021) died three days ago in an unfortunate bicycle accident. I don’t know if the world is a better place thanks to his flashy, in-your-face architecture, but his Liberty Place project, once the tallest in Philadelphia, does not make the city a better place. Ostensibly a take-off of the Chrysler Building, the pair of skyscrapers has always struck me as an uncomfortable presence on the skyline. First off all, Philadelphia has always had its own distinctive tall buildings, beginning with John McArthur, Jr.’s city hall tower (1894), Howe & Lescaze’s PSFS Building (1932), and Ritter & Shay’s U. S. Customs House (1934), so an ersatz New York tower seems out of place. Unlike Van Alen’s Art Deco original, Jahn’s building is modernist, and it suffers a problem common to most modernist work, that is, its big formal moves are unsupported by appropriate detail. There are no equivalents to the Chrysler’s hood-ornament eagle heads, the hubcap decorations, and the sunburst spire. The result is like a preliminary sketch–or a rough plasticine model. Moreover, to make matters worse, there are two towers (built in 1987 and 1990), which undercuts the effect. It is possible to make beautiful twin towers, as Emery Roth’s 1930s San Remo and El Dorado apartment buildings in Manhattan demonstrate, but there is nothing evocative about Jahn’s dumpy pair.

THE FOG OF LIFE

by Witold | May 6, 2021 | Urbanism

A recent conversation on GoodFellows, a podcast from the Hoover Institution, concerned Niall Ferguson’s recent book Doom, and included a comparison between military and civilian planning. This brought to mind what I have always thought was a weakness of the discipline of city planning. Good military planning, as I understand it, is based on preparing for “what if,” that is, developing different scenarios. What if this happens, or that happens? City planning is different, more like advocacy, that is, what should happen. This advocacy is based on certainties: open space is good, density is good—or bad, depending. The problem is that what planners think should happen—separation of pedestrians and cars, superblocks, megastructures—often runs into trouble when it hits the fog of life. Louis Kahn posited a city of mammoth parking structures, whereas Uber reduces the need for car ownership; Paul Rudolph imagined megastructures, whereas cities grow in unexpected directions—small increments help. Years ago, Jane Jacobs pointed out that the city was much too complicated to succumb to simple nostrums; better by far to learn from what was actually happening on the ground.

THE LATEST