A GOOD CAUSE

by Witold | Oct 15, 2021 | Design, Modern life

Home: A Celebration, just published by Rizzoli, is a beautiful book in a good cause; it’s a fundraiser for No Kid Hungry. The interior decorator Charlotte Moss has brought together essays, poems, sketches, and photographs by a variety of authors, including Joyce Carol Oates, Isaac Mizrahi, Annie Leibovitz, Julian Fellowes, Bette Midler, John Grisham, and Alice Waters. There are a few architects, too: Marc Appleton, Michael Imber, Tom Kligerman. And yours truly.

MISPRINT

by Witold | Sep 29, 2021 | Housing

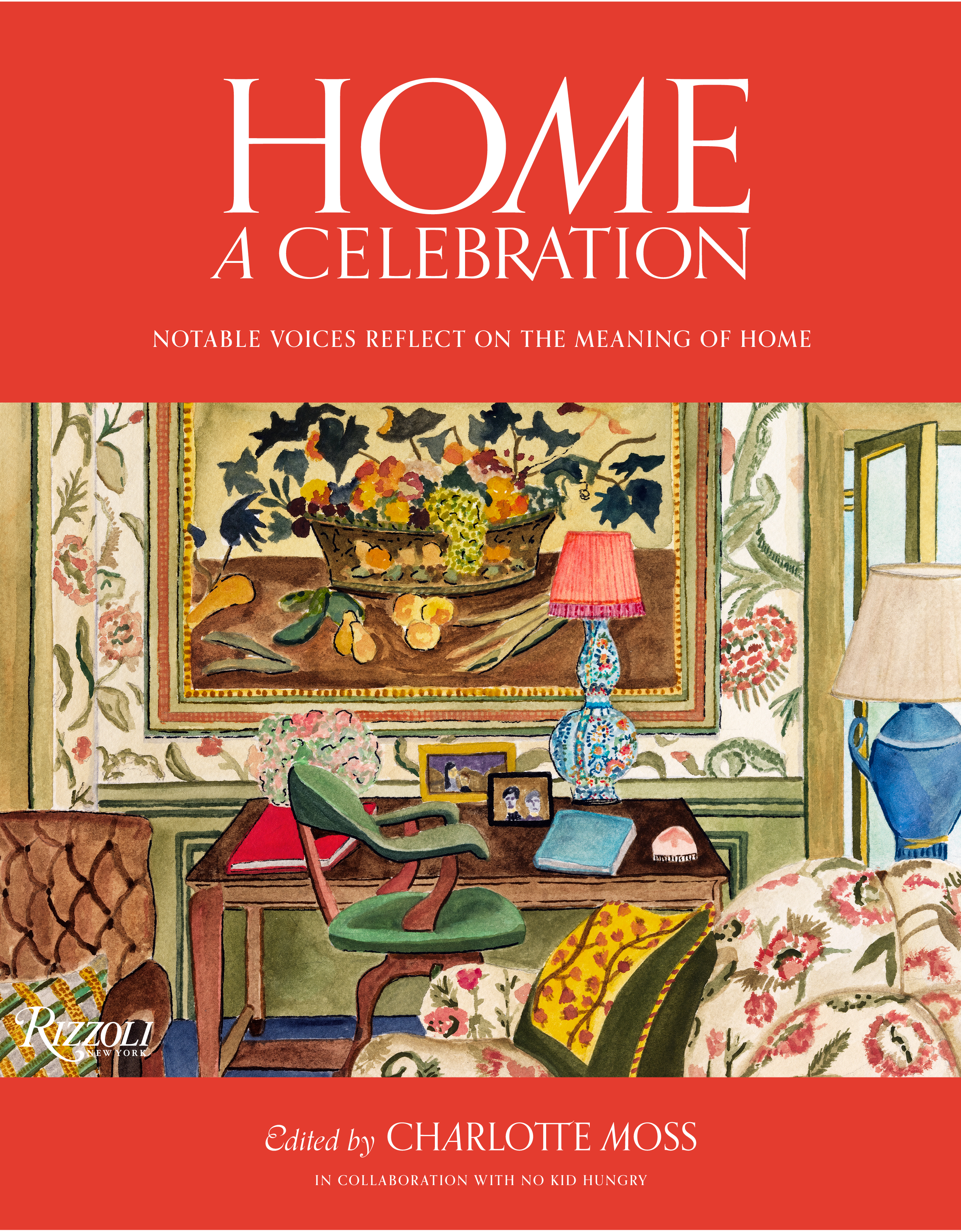

A breathless article in the New York Times writes: “Mr. Hernández and his family are moving to a new home on the outskirts of Nacajuca, Mexico: a sleek, 500-square-foot building with two bedrooms, a finished kitchen and bath, and indoor plumbing. What’s most unusual about the home is that it was made with an 11-foot-tall three-dimensional printer.” Housing crisis? No problem, high tech comes to the rescue! The report is rather sparse on details, but as far as I can make out, the 3D printer spits out the walls and partitions using “Lavacrete,” a concrete-like material. That’s it; the foundations, concrete slab, roof, doors, windows, the “finished kitchen and bath, and indoor plumbing,” and so on, are produced conventionally, so it’s hard to see where the vaunted savings come in. Even if the walls are cheaper—which is far from clear—that would make a minuscule dent in the overall price of the house. In a North American production home, total construction cost accounts for only about one quarter of the selling price, depending on land cost. One quarter.

COMFORT

by Witold | Sep 21, 2021 | Design

“And really, isn’t that what design is meant to do? Challenge us, provoke us, unsettle our expectations. Comfort is welcome. But discomfort can be, too,” concludes a recent editorial in the New York Times’ T Magazine. Oh, really? That’s what design is meant to do? A certain kind of architect and designer—or in this case, magazine editor—considers comfort to be the equivalent of complacency. Or is this just a rationalization, a way to justify exposing concrete, painting surfaces black, leaving out upholstery? No one should confuse comfort with good design; comfort is not sufficient, but it is required. And it is difficult. Much easier to “challenge, provoke, and unsettle,” and pretend that “discomfort is welcome.” What rubbish.

Photo: Zig-Zag Chair, Gerrit Rietveld, 1930s

INSTRUCTION AND INSPIRATION

by Witold | Sep 5, 2021 | Architects, Architecture

A reader recently wrote to me citing Frank Lloyd Wright as a model for the future. “Wright’s discipline itself offers us an antidote to the wandering efforts of rudderless students: it can be understood and undertaken by those with a little personal aptitude and a readiness for hard work to design buildings of real point, character, freshness, and charm.” How likely is a Wright Revival? Historical examples of revivals abound: Inigo Jones revived Palladio, Wren revived Bramante, Lutyens revived Wren. More recently, Richard Meier launched his career by reviving early Corbusier, Tadao Ando learned a lot from Kahn, and Thomas Phifer has revisited Mies. What is striking about the revivalists cited above is that they are all architects of the first rank who found inspiration in the work of an earlier master. Inspiration, not instruction. The reason that a Wright Revival is unlikely is that his work and writings are didactic—my way is the right way, the only way—which tends to produce disciples and followers, but does not necessarily inspire independent creative talents. The successful model for a revival is capacious, opening doors rather than setting limits, acting as a springboard rather than a template.

Photo: Smith House (Richard Meier), 1965-67

MOXIE

by Witold | Aug 31, 2021 | Modern life

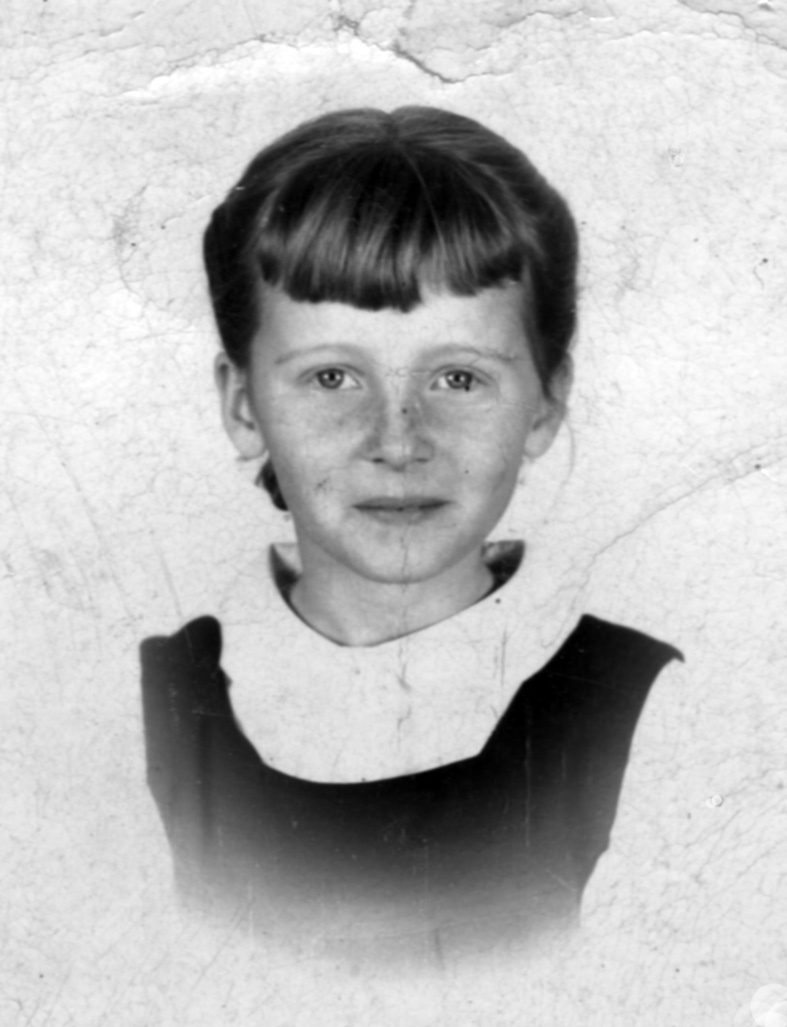

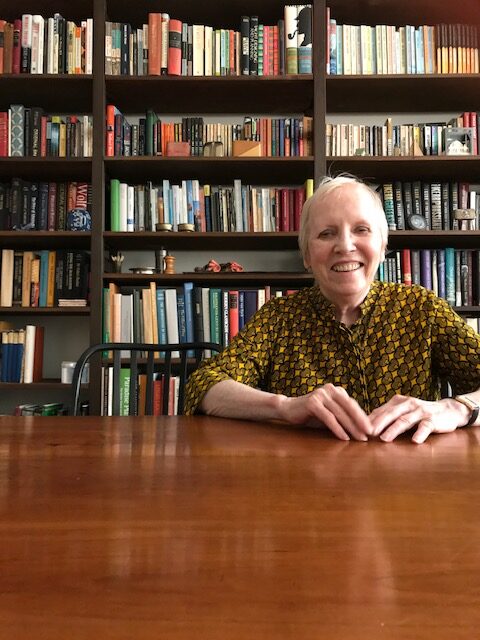

It is eight weeks since Shirley died. I still can’t get used to saying “I” and “mine” rather than “we” and “our.”

I look at old photographs a lot. This is one when she was a student in a convent school with the sisters of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame in Montreal. She is ten and all her best qualities are already in evidence in her forthright gaze: good humor, realism, intelligence, fortitude. And moxie—she is fearless.

FUNERAL BLUES

by Witold | Jul 10, 2021 | Modern life

SHIRLEY GLORIA

by Witold | Jul 7, 2021 | Modern life

This morning at two o’clock, my wife Shirley died peacefully in her sleep. She’d been at home under hospice care for six weeks after an acute failure of her mitral heart valve. She was very brave and put up with the indignities of bed-care with good humor and without complaint, or at least without too much. Willful as always, one of her last acts was to turn down a medication I was offering her. She must have known she no longer needed it. It was a long goodbye and her death was hardly unexpected. I shan’t say “I’ll miss her”; how can you miss someone who remains an integral part of you? We had been married almost fifty years—I can no longer tell where she stops and I begin, and vice versa. During the last weeks she wanted no music in the house. Now Casals and Bach comfort me.

An afterthought: The worst thing about death is its finality. The door is closed. There is no rewind or edit. Whatever was was, for all time.

And another: The advantage of hospice care is that you get to die on your own terms. In Shirley’s case that meant serious introspection, no visitors, little talk, almost no food except a little wine, and no entertainment. “She needed all her concentration to go quietly,” was how a friend put it.

DRESS AND DECOR

by Witold | Jun 22, 2021 | Architecture

I recently wrote an essay for the catalog of the Polish pavilion at the London Design Biennale 2021. The theme of the exhibit of handwoven textiles was “The Clothed Home,” and the title of my essay was “Dress and Decor.” I think I first made this connection when I was writing Home, and looking at paintings of interiors. François Boucher’s enchanting “La Toilette,” painted in 1742 and currently hanging in the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza of Madrid, was one of these. I was struck with how the dress of the two women, and the materials of the decor—the Chinese folding screen, the silk wallpaper, the upholstery of the slipper chair, even the moldings of the fireplace mantel—were visually all of a piece. This was not simply a painterly conceit. Dress and the decor used similar fabrics and techniques, and more important, they were governed by the same Taste. Boucher painted during the period we call Rococo, but a similar concordance occurred in later periods: Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, Art Deco, the early Modern Movement, and so on. In other words, we have always dressed ourselves and then decorated—dressed—our homes to suit.

ARCHITECTURE AND ART

by Witold | Jun 20, 2021 | Architecture

Several weeks ago I was interviewed by Carolyn Stewart for American Purpose. One of her questions was: “Are there any overlooked aspects of classical architecture – whether an element of design, function, or ethos – that deserve to be rediscovered in the current moment?” That reminded me of President Trump’s recent executive order promoting the classical style for federal buildings, subsequently withdrawn by the Biden administration. The idea that we should learn from the past raised the ire of many at the time, but yesterday’s buildings do offer real lessons. One concerns the presence of art, a long tradition in architecture. Can you imagine the facade of Notre-Dame without the sculptural figures, or Palladio’s Villa Barbaro without Veronese’s frescoes and Marcantonio Barbaro’s facade decorations? Or, to cite a more recent example, Raymond Hood’s RCA Building in Rockefeller Center without Lee Lawrie’s evocative bas-reliefs. In the name of renouncing the past—and denouncing anything that smacks of decoration—modernism has largely done away with art, the lonely Henry Moore stranded on a plaza, notwithstanding. The problem is that when you strip away figural and allegorical ornament, what is left are mute building materials, mechanical-looking details, and abstract space. Sigfried Giedion extolled the virtues of pure space, but while space may fascinate the art critic it conveys little to the public. Ever since the Parthenon’s metopes, buildings have spoken through art, whether it is a statue of Justice in a courthouse, or of Euterpe the Muse of music in a concert hall; the latter is pictured here on the entrance facade of the Teatro Pérez Galdós in Las Palmas (built in 1890 by Francisco Jareño, architect of the National Library in Madrid). The presence of allegorical ornament not only increases visual delight, it does something even more important: it adds meaning.

COUNTERFACTUAL

by Witold | Jun 16, 2021 | Architecture

Architectural history is sometimes recounted as if it evolved autonomously, architects attacking and solving architectural problems largely of their own devising. But because buildings are large, complicated, and expensive, architecture is subject—more than other arts—to outside forces, economic, political, social. Here’s a historical counterfactual. What if the Depression and the Second World War hadn’t happened? What if construction hadn’t been halted for more than a decade and the American modernist movement of the Twenties and Thirties that produced the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center, the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Walter Reed Naval Medical Center, Omaha’s Union Station and Los Angeles City Hall, had not abruptly been halted but had blossomed further instead? What if Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius had stayed in Germany, and remained avant-garde outsiders, entering competitions rather than building? The story of architecture would have taken a very different turn.

Photo: Union Station, Omaha. Gilbert Stanley Underwood, arch. (1931)

THE LATEST