MOYNIHAN HALL, CONT’D.

by Witold | Apr 30, 2022 | Architecture, Design

A little more about the question of style. Style is not about what you say but how you say it, not about content but delivery. The impersonal announcements of voicemail, or of a public address system, are almost pure content, there is very little delivery beyond a certain functional brevity. But an actual person speaking includes variable emphasis of tone and volume, facial expressions, hand gestures, asides, jokes, and so on. The effect can be conversational or stentorian, formal or informal, intimate or cold, depending on the style. That is why the word was originally used in the context of rhetoric. Architectural style is comparable. Pennoyer’s clock in Moynihan Hall is sometimes described as Art Deco, which I suppose it suggests, although the clock face is as modern as a Max Bill timepiece. Art Deco has a frivolous side, but this clock is monochrome matte grey, so rather serious, although the telescoping form is sculptural, so it’s not completely serious. “You need to know the time but there is more to life than train schedules.” The decoration is restrained, but it’s there, which gives us something to look at. That is what is missing in the architecture of the hall—there is nothing to look at. This is not really SOM’s fault, or at least it’s not because they made mistakes. Once committed to a modern architectural vocabulary, the result was preordained. Modernist architects eschew style, or rather, they work in only one style, which can be characterized as “functional,” “clean,” or “no-nonsense.” Just the facts, ma’am. But the hall of an important railroad station in an important city demands more than facts. That is what the architects who designed the great stations of the Moderne era—Thirtieth Street in Philadelphia, Union Station in Omaha, Union Terminal in Cincinnati, understood.

MOYNIHAN HALL

by Witold | Apr 29, 2022 | Architecture

When I was a practicing architect and a structural problem arose I would ask my engineer friend, Emmanuel Leon, for advice. Once I was designing a house which required a long span. In his pragmatic Filipino way he asked me, “Do you want it cheap or architectural?” (I wanted the latter and he designed an upside-down king post truss.) I thought of Emmanuel when I walked into Penn Station in New York recently. It was my first trip on Amtrak in several years, and I was looking forward to seeing the much lauded station hall, which is in the old Farley post office building. I was disappointed. For one thing, the space was small. My train had left Philadelphia’s Thirtieth Street Station (designed by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White in 1927-33), which has a majestic hall, and this space was puny by comparison. And the steel trusses overhead were definitely utilitarian rather than architectural (they had originally spanned the mailroom). I had read plaudits about the suspended clock in the center of the hall, designed by Peter Pennoyer. It is very handsome, and it highlights one of the main drawbacks of its surroundings; unlike the clock, or Thirtieth Street Station, for that matter, the new station has no sense of style. The generic architecture (designed by SOM) could be an office building lobby or a shopping mall just about anywhere. And unlike Thirtieth Street, which has long oak benches, there is nowhere to sit except a claustrophobic “waiting room.” So passengers sprawl on the floor. Not attractive. Did I mention that it’s called Moynihan Hall, after the great senator? The name is displayed everywhere, over and over again, as if that would make up for the pedestrian design. Moynihan, who had an eye for architecture, would wince.

A VISIT

by Witold | Mar 26, 2022 | Modern life

Sometimes I imagine that Shirley comes home. At least to visit. She looks around our loft, in which little has changed in nine months. “That’s new,” she says, pointing to a framed photograph in the bookcase. It is of her, sitting at the table, in front of that same bookcase. I got it to balance the old photograph of her, taken in the sixties, before we met; glamorous with long hair and large sunglasses. “Why are all my glasses still here?” she asks pointing to a half dozen cases—Robert Marc, Iyoko-Inyaké, Ray-Ban. I sense disapproval in her voice. We go upstairs to the bedroom. She looks in the closet. “You’ve kept my Zuri dresses and Trippen shoes,” she says. “And all my beautiful coats. Why? Shouldn’t you get rid of them?” I am abashed, but I don’t know how to do that. “Maybe later,” I tell her.

Photo: Kenyan print dress by Zuri

CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER (1936-2022)

by Witold | Mar 24, 2022 | Architects

When I was a student at McGill, my friend Ralph Bergman and I started a magazine, Asterisk, actually it was named *. The second issue, this was 1964, included an article by Alexander and the architect B.V. Doshi on designing a village in India. A couple of years later, when I was working on my thesis, another classmate, Richard Rabnett, had come across HIDECS, Alexander’s computer program for ordering criteria in architectural design. It was in FORTRAN, and we laboriously entered our information onto punch cards, although we never could get the program to run (years later I learned that HIDECS was flawed and could not actually run). My next encounter with Alexander was in 1978 in Mexico City. I had been invited to speak at a symposium at the Universidad Nacional—Alexander would deliver the keynote. Expecting the usual sparse turnout I was amazed to find an audience of several hundred excited students—not there for me, I hasten to add. The previous year, Alexander had published A Pattern Language, and it had turned him into an international star. I had a copy, of course. One of his principles was that design could not be disconnected from the actual process of construction. At the time, my wife and I were building our own house, an experience that validated—at least for me—the truth of this assertion: many of our most important design decisions were made on the building site not on paper. I followed Alexander’s career through his many books, which still remain a part of my reduced library. In 1994, I had an opportunity to meet the man when he was awarded the Seaside Prize. During a conversation he said something that has stuck with me: everything that we see in our surroundings—everything—either slightly raises our spirits or slightly lowers them. Our paths last crossed in 2009, when he was awarded the Vincent J. Scully Prize. Alexander, who was now living in England, was down with pneumonia and unable to attend, and I joined a panel of previous laureates to speak about the man and his work. In my remarks I compared Alexander to Jane Jacobs. “I think there’s a sense in which both of them see the world as very, very messy, and they see the charm in that. And they’re on the one hand looking for order, but also at the same time very worried that too much order will lose the thing that you actually value.” This creative tension is present both in the insightful books that he wrote and the beautiful buildings that he built.

A HOLIDAY FROM HISTORY

by Witold | Mar 22, 2022 | Architecture

I was listening to a conversation between Peter Robinson and Bari Weiss on the Hoover Institution’s Uncommon Knowledge podcast. I was brought up short by Weiss’s phrase: “a holiday from history.” Weiss and Robinson were talking about what she called The Great Unraveling, but it struck me that a “holiday from history” could easily refer to architecture, which since roughly the 1920s has turned away from the past. Where once architects had learned their art in part by studying history, whether in books or through travel, they now had their vision resolutely focused in only one direction—the future. In that way, design was simplified. No need to take on Mr. Bramante or Mr. Wren (to use a Hemingwayesque locution)—you were free to make your own rules. This was at first exciting, and one sees this excitement in the early work of Corbusier and Mendelsohn. But succeeding generations have found the holiday from history could also be a bit of a bore, as well as a challenge—it is not so easy to continually reinvent an architecture “for our time.” All holidays come to an end, of course. Will architects return to a more tried and true method: looking back in order to move forward, in James Stirling’s words?

NOT QUITE ALONE

by Witold | Mar 19, 2022 | Modern life

It is a curious thing, this new solitude of mine. More than one person has told me “You will always have the memories of your life together.” Well, I suppose that’s true, but life exists in the present, not the past, and it is in my daily routines that Shirley is most present. After almost five decades, many of my habits are entwined with hers: how I cook, or shop, or simply look at the world. There is a downside: many of the things we did together—eating out, traveling, going to a museum or a concert, watching Jeopardy—have lost their appeal. These things only remind me that she is no longer able to enjoy them. But every time I do the laundry I remember her instructions; take care of this, make sure of that. I am alone, and yet not quite.

Photo:Castellana Hilton, Madrid, April 1976

THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY

by Witold | Mar 16, 2022 | Architects

Robert A. M. Stern has just published Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture. This is not a review; I’ve only read the first chapter—on Amazon—which details the author’s childhood. But Stern’s book is not exactly an autobiography; the publisher calls it “a personal and candid assessment of contemporary architecture and his fifty years of practice.” In fact, architectural memoirs are few and far between. With the exception of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famously unreliable An Autobiography, I only know of two modern examples, Nathaniel Owings’s The Spaces in Between: An Architect’s Journey (1973), and A. Eugene Kohn’s The World by Design: The Story of a Global Architecture Firm (2019). I think there are a number of explanations. Writers keep journals; architects carry sketchbooks—theirs is a visual not a literary imagination. More to the point, architecture is a profession, which makes candid recollections tricky, like telling tales out of school. I once asked Gene Kohn about a recent KPF project that seemed to me awkward. “Yes,” he answered. “That one got away from us.” We were, of course, speaking privately. Difficult clients, design mistakes, and missed opportunities are a part of every architect’s “journey,” but they are always discreetly kept out of the public eye.

NOT INTERESTED

by Witold | Mar 4, 2022 | Modern life

In this difficult time the famous Leon Trotsky quote comes to mind: “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

CRYSTAL CITY

by Witold | Feb 15, 2022 | Architects, Architecture, Modern life

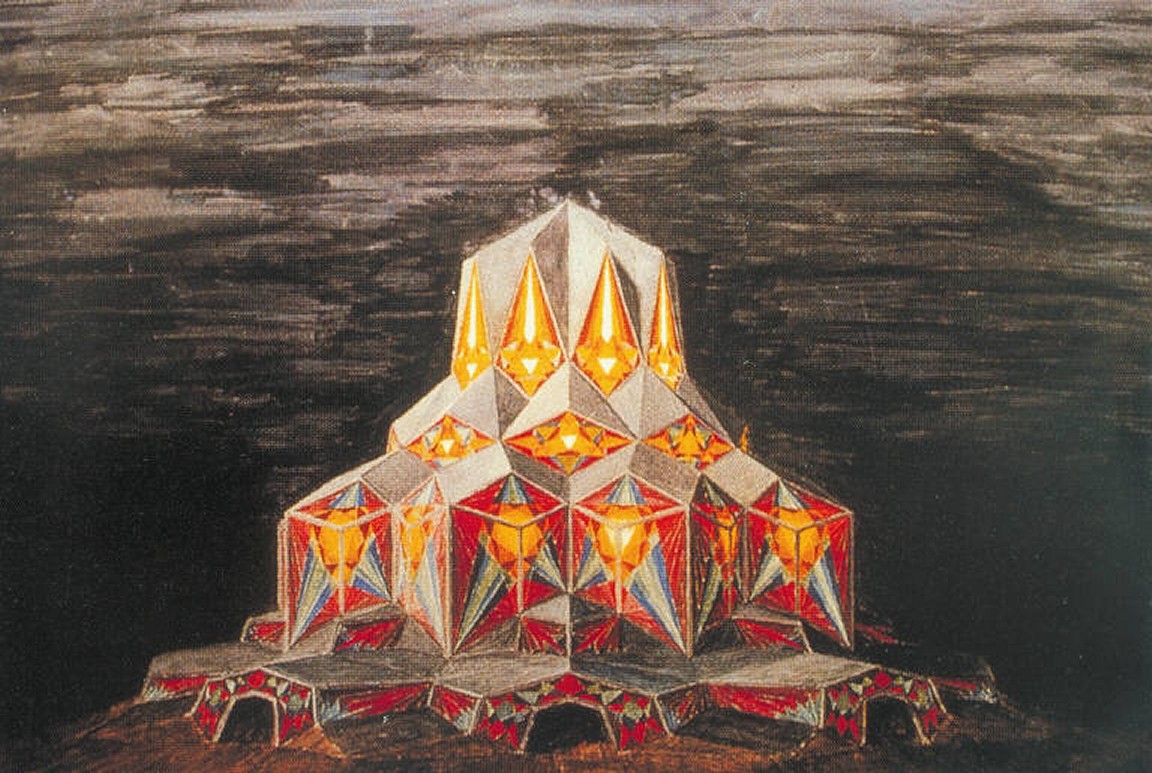

Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915) was a German writer of the turn of the nineteenth century; today we would call him a sci-fi author. In 1914 he wrote a novel with the unwieldily title The Grey Cloth and Ten Percent of White. The protagonist is an architect, more specifically a “glass architect,” and Scheerbart dedicated the book to Bruno Taut, a Berlin architect who promoted the idea of revolutionary all-glass buildings. Glasarchitektur (the title of another Scheerbart book) was an avant-garde obsession; Taut imagined “glowing crystal houses and floating, ever-changing glass ornaments.” When I look out my window I can see his crystal city come to life. It is certainly glowing, especially on a sunny day. Ever-changing? Well sort of. What is missing is the color and jewel-like qualities of Taut’s rather beautiful sketches. And the mute glass boxes undermine traditional architectural qualities such as mass and shadow, structure and weight, but I suppose that was the whole point of glasarchitektur.

Image: “The City Crown,” Bruno Taut, 1919.

HOUSE MEMORY

by Witold | Feb 7, 2022 | Architects, Architecture

I met Marcel Breuer in October 1973 at his home in New Canaan, Connecticut. He designed the house, known as Breuer House II, in 1951, a low-slung affair with rough fieldstone walls, a slate floor, and an unpainted wood ceiling. Plate-glass windows looked out on a Calder stabile on the lawn, and nearby woods. We ate lunch sitting on Cesca chairs at a table that consisted of a thick granite slab. Breuer himself, 71, was courtly and engaging. Philip Johnson once called him a “peasant mannerist,” and there was something appealingly simple in his demeanor, as in the house itself. I admire Breuer’s houses, but that visit apart I have never actually seen one—I know them only from black-and-white photographs in books. So, when James S. Russell writes in the New York Times on the occasion of the demolition of Breuer’s Geller House, “Regrettably, the lessons such houses teach are lost as they grow fewer all the time,” I must disagree. The demolition of a public building—or any building in public view—can be like the loss of an old friend, but when a private house in rural surroundings is torn down, it is more like the proverbial tree falling unheard in the forest. I was lucky to see Breuer House II—he sold it three years later. In 2007, the house was disfigured—to my eye—by an intrusive glass addition designed by Toshiko Mori, but my memory of the visit and the old black and white photos taken when it was occupied by Constance and Marcel Breuer are still there. That house will live on.

Photo: Alvaro Ortega, Jon Boone, Breuer, WR and my old BMW 1600

THE LATEST