THIS IS THE PLACE

by elementor | Oct 26, 2022 | Architecture, Modern life

Architects and town planners often refer to a “sense of place” as a mark of authenticity. For example, Central Park has a sense of place, but a Walmart parking lot doesn’t. Nothing is as bad as placelessness—the term “placeless sprawl” appears in the first sentence of the Charter of the New Urbanism. It sounds like a logical extension to go from valuing a “sense of place” to “place-making.” But I’m not so sure. When Brigham Young arrived at Salt Lake Valley he is said to have exclaimed, “This is the place!” Young had the benefit of a previous celestial vision. I remember the first time I went to Chez Panisse, or saw the Empire State Building, or walked into the Guggenheim Museum; it was not only a question of design but of memory. We have all been to airport bars that work hard at creating a sense of place with period photos, team pennants, and other knickknacks. The harder they work at it, the more placeless they seem. On the other hand, the Cherry Street Tavern around the corner from where I live is for me a real place, not just because it has a nice wooden bar and old Bob Dylan posters, but because it is where I frequently go for lunch. Place is in the eye of the beholder. And however placeless sprawl may appear to the outsider, if you live there, when you arrive at your suburban home, you think “This is the place.”

READ ALL ABOUT IT

by elementor | Oct 16, 2022 | Architecture

I came across this confident statement in the September issue of New York Review of Architecture, in a rather breathless review of a recent book about Aline and Eero Saarinen: “It is through media, of course, that we primarily consume architecture.” I was brought up short. How preposterous, I said to myself. But on second thought I realized that it was all too true. If there is an audience for architecture—and judging from the almost total absence of architecture columns in the mainstream press one has to be doubtful—it’s likely that its chief connection with architecture is through media rather than first-hand experience. And, consumers, as opposed to building occupants, need to be amused, tittilated, and entertained. The experience of a great building is complex and involves tactile qualities as well as historical memory, attributes that are difficult to convey on a iPhone. I suppose if Steen Eiler Rasmussen were writing his classic handbook today he would have to call it Consuming Architecture. How sad.

PHILADELPHIA SECESSION

by elementor | Sep 30, 2022 | Architecture

The other day, my friend Jonathan Barnett and I were walking down 23rd Street when our attention was drawn to an unusual building on Manning Street, one of those narrow alleys that are common in Philadelphia. Obviously very new, the building caught our eye for a number of reasons. First, the walls were brick, at a time when virtually all infill housing in the city is glass with perhaps a scattering of metal siding. And this brick was not the usual red, but lightly glazed yellow. Second, the regular composition of rectangular openings punched in the facade of this three-story box was similarly unusual at a time when architects are bending over backward to avoid regularity, let alone symmetry. The box-with-openings reminded me of the Haus Wittgenstein in Vienna, designed by Paul Engelman and Ludwig Wittgenstein for the latter’s sister in 1925-28. But the Manning Street building also recalls an earlier period: the Vienna Secession. The windows, which are set into large opening are framed by black L-shaped panels ornamented with geometrical patterns. Ornament! That really set this interesting little building apart. The architects are a local firm, Stanev Potts; Petra Stanev and Stephan Potts. Chapeau!

Photo credit: Ryan Lohbauer

NIGHT

by elementor | Sep 19, 2022 | Architecture

Love has gone and left me and the days are

all alike;

Eat I must, and sleep I will,–and would that

night were here!

–Edna St.Vincent Millay

THERE’S AN APP FOR THAT

by elementor | Sep 16, 2022 | Modern life

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words. Tell that to today’s museum curators, who insist of covering gallery walls with words, identifying the picture, who painted it and when, and of course who donated it. At the very least. There are also entire chunks of text making sure that we understand why this art is important. The result is that museum goers are caught up in reading, or listening if they have rented an audio guide, anything but looking. What a shame. I am with Albert C. Barnes, who insisted that his collection not have any identifying labels. Nothing but the art itself. The curators at the Barnes Foundation are legally constrained from adding text to the wall—in any case, there is no room—so they have helpfully created an app, Barnes Focus. Now people can stare at their phones instead of looking at the paintings.

Photo: Gallery in Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

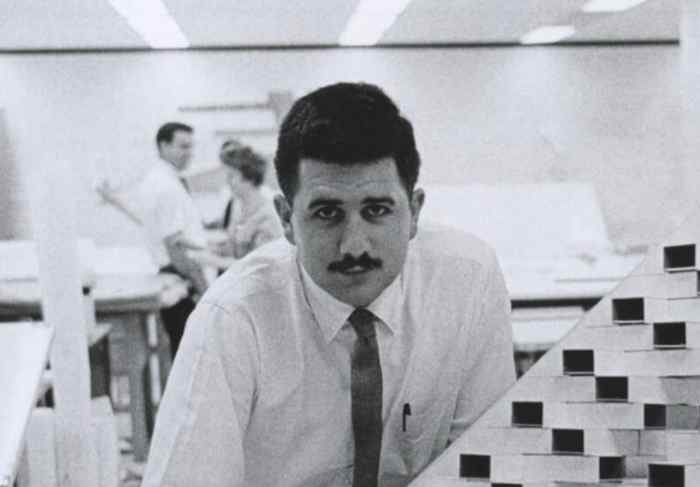

CAREERS

by Witold | Aug 26, 2022 | Architects

Moshe Safdie has just donated his architectural archive of correspondence, drawings, and models, as well as his apartment in Habitat, to his alma mater, McGill University. His is a remarkable career, not least for its long span. Of course Safdie started young, he was only 29 when Habitat—his first project!—propelled him into the limelight. Most architects who experience a break-out project do so at a relatively advanced age—Louis Kahn was 52 when he came to the public’s attention, Frank Gehry was 49. Edwin Lutyens, an exception like Safdie, skipped school and designed his first house at 18, and was nationally known by the time he reached his mid-30s (he died at 74). The one architect I can think of who bears direct comparison with Safdie is Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Prairie Houses date from his 30s, and whose career likewise exceeded 50 years. Of course, he lived to be 91; Safdie is 84 and going strong. Sto lat, Moshe, sto lat.

Photo: Moshe Safdie with Habitat model, c. 1964.

REVIVALS VS. TRANSPLANTS

by Witold | Jul 18, 2022 | Architecture

Revivalism in architecture refers to a style that consciously echoes or evokes the style of a previous era. This blurs an important distinction. The Italian Renaissance and the British Gothic Revival were echoing the styles of earlier eras, earlier local eras. The Greek Revival, on the other hand, whether it occurred in Berlin, Edinburgh, or Philadelphia, was a foreign style from far away; it was a transplant. That did not mean that it was less authentic, but it did give it a different meaning. When Robert A. M. Stern built Franklin and Murray colleges at Yale in 2017, he was reviving James Gamble Rogers’s Collegiate Gothic of the previous century. But Rogers had not revived a local tradition; his inspiration was a collection of postcards and photographs of Oxbridge colleges (that he had not visited). He was transplanting.

WEIRDOS

by Witold | Jul 2, 2022 | Modern life

A “nation of weirdos” is how Michael Brendan Doherty characterized the United States the other day on The Editors Fourth of July podcast. It was meant kindly. The weirdos have included Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Steve Jobs, as well as the inventors of the hula hoop, the smoothie, and the pet rock. The pursuit of happiness takes many unexpected twists and turns.

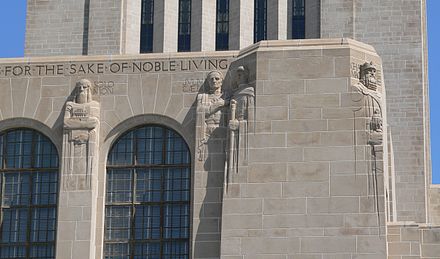

DECADENCE

by Witold | Jun 18, 2022 | Architecture

I was listening to some old interviews on Tyler Cowen’s podcast, Conversations with Tyler, and came across this one, with Ross Douthat, made in March, 2020. Douthat made this observation about architecture: “I would say that, basically, the place that modern architecture has ended up and the traditionalist alternative are both sort of decadent . . .” I found that interesting, since modernism and traditionalism are usually described as a divide rather than as evidence of the same thing. Decadence in modernism is apparent in the (fruitless) search for unceasing novelty, that takes architects into increasingly obscure ratholes. In traditionalism decadence can be the result of a sometimes fawning admiration for the past, that inhibits the sort of originality that—in different ways—fueled the architecture of Michelangelo and Borromini, or more recently of Bertram Goodhue.

Photo: Nebraska State Capitol (Bertrand Grosvenor Goodhue, architect, 1920-32)

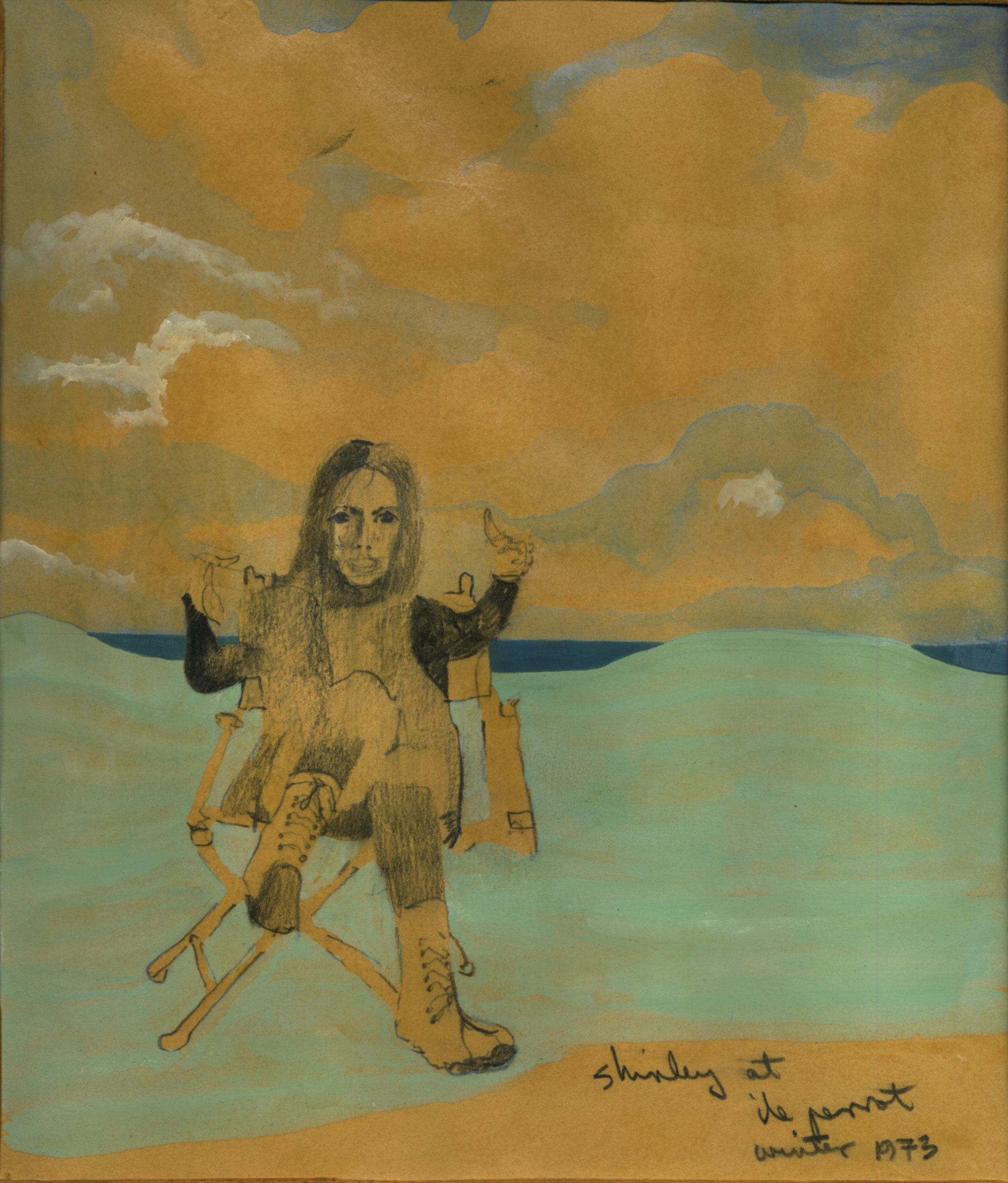

HIS MASTER’S VOICE

by Witold | May 15, 2022 | Modern life

An odd thing happened to me the other day. I was talking to someone and I used an expression that I had never used before, but was something that Shirley might have a said. Even as I spoke I recognized her voice and for a weird split-second I felt like a ventriloquist’s dummy. Not necessarily a bad thing, I thought to myself.

THE LATEST