PHENOMENA

by Witold | May 1, 2016 | Architects, Architecture

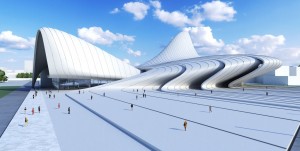

Azerbaijan Cultural Center, Baku (Zaha Hadid, arch.)

I came across the following passage recently.

There have always been dazzling personalities that flashed out of the surrounding gloom like the writing on the wall at the great king’s feast; but they are not manifestations of healthy art. They are phenomena. The sanest, most wholesome art is that which is the heritage of all the people, the natural language through which they express their joy of life, their achievement of just living; and this is civilization,—not commercial enterprises, not industrial activity, not the amassing of fabulous wealth, not increase of population or of empire. These may accompany civilization, but they do not prove it.

This was written by Ralph Adams Cram, the introduction to his Church Building, published in 1899. I read this at the same time as numerous fulsome encomia appeared in the media on the occasion of the death of Zaha Hadid, certainly a “dazzling personality.” She was also, in Cram’s sense, a phenomenon. Like so many leading architects today, her work was personal, eccentric, and idiosyncratic, the very opposite of a natural language, a popular heritage. Not an architecture grounded in a particular place, like Gaudí’s equally eccentric buildings, but global in nature, built in faraway lands for faraway people often of fabulous wealth. Accompanying civilization, but not proving it.

MOUNT CUBA

by Witold | Apr 21, 2016 | Architects, Architecture

The other day we drove to Mount Cuba, a horticultural center in Delaware. The forest garden is part of an estate built in the 1930s by Lammot du Pont Copeland and his wife Pamela, a branch of the mighty Delaware family. We went to look at the trillium garden, but I was also impressed by the house, a very large Colonial Revival mansion that was completed in 1937. The beautiful brick architecture was exquisite, simple to the point of distillation. The design was the work of Victorine and Samuel Homsey. Samuel (1904-1994), a native of Boston, graduated from MIT and met and married Victorine du Pont (1900-98), who had studied at the Cambridge School of Domestic and Landscape Architecture for Women. They set up shop in Delaware, which is where Victorine had family contacts; theirs was probably the first husband-and-wife practice in the United States. In addition to Mount Cuba they were responsible for several building on the nearby Du Pont estate, Winterthur, as well as the Delaware Art Museum. The Museum of Modern Art selected their house design to represent the International Style for the 1938 Paris Exhibition, but they were not modernist converts. “We certainly are not modern if that means following worshipfully the so called functional or international style,” wrote Victorine. “Nor do we follow with blind admiration the great designers of earlier periods. We try to work out each job as a totally separate problem and to divorce from our minds any preconceived idea of style.” Eclecticism is maligned today, but looking at Mount Cuba one can only admire its rigor and sense of conviction.

The other day we drove to Mount Cuba, a horticultural center in Delaware. The forest garden is part of an estate built in the 1930s by Lammot du Pont Copeland and his wife Pamela, a branch of the mighty Delaware family. We went to look at the trillium garden, but I was also impressed by the house, a very large Colonial Revival mansion that was completed in 1937. The beautiful brick architecture was exquisite, simple to the point of distillation. The design was the work of Victorine and Samuel Homsey. Samuel (1904-1994), a native of Boston, graduated from MIT and met and married Victorine du Pont (1900-98), who had studied at the Cambridge School of Domestic and Landscape Architecture for Women. They set up shop in Delaware, which is where Victorine had family contacts; theirs was probably the first husband-and-wife practice in the United States. In addition to Mount Cuba they were responsible for several building on the nearby Du Pont estate, Winterthur, as well as the Delaware Art Museum. The Museum of Modern Art selected their house design to represent the International Style for the 1938 Paris Exhibition, but they were not modernist converts. “We certainly are not modern if that means following worshipfully the so called functional or international style,” wrote Victorine. “Nor do we follow with blind admiration the great designers of earlier periods. We try to work out each job as a totally separate problem and to divorce from our minds any preconceived idea of style.” Eclecticism is maligned today, but looking at Mount Cuba one can only admire its rigor and sense of conviction.

MEGACITY

by Witold | Apr 3, 2016 | Urbanism

Rather silly op-ed piece in today’s New York Times arguing that the mayoralty of Toronto’s Rob Ford, which made most Torontonians—and Canadians—cringe, was actually a sign of a healthy politic. Toronto, like Montreal, has regional not municipal government, imposed, I hasten to say, not by popular choice but by a provincial fiat. The amalgamation of a traditional central city with its surrounding metropolitan suburbs, is virtually impossible to achieve in the U.S., although it is the dream of many American city planners. Such amalgamation, the argument goes, would spread the advantages and burdens of urbanization over the entire metropolitan population, shifting suburban resources to inner city problems. Sounds like a good thing. Except that when the suburbs outnumber the city, you get a “suburban” dingbat like Rob Ford, who managed to get elected as mayor (and re-elected to his council seat), despite his embarrassing behavior precisely because of his pro-suburb, anti-city policies. Ford was a symptom of urban success? I have never read about Toronto’s “livable suburbs,” or about the “suburbs-that-work.” The image of Toronto is precisely that—the image of a city that is dense, well served by mass transit, safe, efficiently managed. Toronto suburbs are not much different from their American counterparts. The Times article compares Toronto to nearby Detroit (talk about a loaded comparison). The latter is a ring of white suburbs surrounding a majority black city. I can imagine what the Times would say about a Detroit regionally governed by a redneck white (suburban) mayor riding roughshod over his predominantly black city constituents? Amiri Baraka could certainly imagine it. Back in 1993 I was on a Wayne State University panel with the late Newark poet discussing urban issues. In my Canadian naiveté I suggested that Detroit might be better off with a regional government—spread the wealth, etc. Baraka exploded. That would simply place city government back in the hands of the white majority, he remonstrated. A ridiculous suggestion. In 1993, a fresh immigrant to the U.S., I was puzzled by his response. Now I take his point.

Rather silly op-ed piece in today’s New York Times arguing that the mayoralty of Toronto’s Rob Ford, which made most Torontonians—and Canadians—cringe, was actually a sign of a healthy politic. Toronto, like Montreal, has regional not municipal government, imposed, I hasten to say, not by popular choice but by a provincial fiat. The amalgamation of a traditional central city with its surrounding metropolitan suburbs, is virtually impossible to achieve in the U.S., although it is the dream of many American city planners. Such amalgamation, the argument goes, would spread the advantages and burdens of urbanization over the entire metropolitan population, shifting suburban resources to inner city problems. Sounds like a good thing. Except that when the suburbs outnumber the city, you get a “suburban” dingbat like Rob Ford, who managed to get elected as mayor (and re-elected to his council seat), despite his embarrassing behavior precisely because of his pro-suburb, anti-city policies. Ford was a symptom of urban success? I have never read about Toronto’s “livable suburbs,” or about the “suburbs-that-work.” The image of Toronto is precisely that—the image of a city that is dense, well served by mass transit, safe, efficiently managed. Toronto suburbs are not much different from their American counterparts. The Times article compares Toronto to nearby Detroit (talk about a loaded comparison). The latter is a ring of white suburbs surrounding a majority black city. I can imagine what the Times would say about a Detroit regionally governed by a redneck white (suburban) mayor riding roughshod over his predominantly black city constituents? Amiri Baraka could certainly imagine it. Back in 1993 I was on a Wayne State University panel with the late Newark poet discussing urban issues. In my Canadian naiveté I suggested that Detroit might be better off with a regional government—spread the wealth, etc. Baraka exploded. That would simply place city government back in the hands of the white majority, he remonstrated. A ridiculous suggestion. In 1993, a fresh immigrant to the U.S., I was puzzled by his response. Now I take his point.

HOOPLA

by Witold | Mar 21, 2016 | Architecture, Modern life

The newly completed Oculus in Manhattan is not just misnamed (an oculus is a round opening, not a slit) it is misconceived. It is not a question of design, or execution, or cost, but rather of the entire concept. Does a daily commute really require this level of architectural rhetoric? Even if this were a substitute for Penn Station, it would be a dubious proposition. It made sense for our forbears to celebrate long distance train travel, when railroad terminals really were the “gateways to the city.” Today, that is no longer the case. Even air travel has become a mundane, everyday affair. just look at how plane travelers dress—for comfort, not for distinction. This does not mean that an airline terminal—or a train station, for that matter—needs to be banal, the equivalent of architectural Muzak. But maybe Scarlatti rather than Wagner is in order? I recall my first experience of Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, some thirty years ago. It was a comfortable relaxing (and quiet) place, just right for the jet lagged intercontinental traveler. Does the weary commuter really need Calatrava’s over-heated hoopla? I think not.

The newly completed Oculus in Manhattan is not just misnamed (an oculus is a round opening, not a slit) it is misconceived. It is not a question of design, or execution, or cost, but rather of the entire concept. Does a daily commute really require this level of architectural rhetoric? Even if this were a substitute for Penn Station, it would be a dubious proposition. It made sense for our forbears to celebrate long distance train travel, when railroad terminals really were the “gateways to the city.” Today, that is no longer the case. Even air travel has become a mundane, everyday affair. just look at how plane travelers dress—for comfort, not for distinction. This does not mean that an airline terminal—or a train station, for that matter—needs to be banal, the equivalent of architectural Muzak. But maybe Scarlatti rather than Wagner is in order? I recall my first experience of Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, some thirty years ago. It was a comfortable relaxing (and quiet) place, just right for the jet lagged intercontinental traveler. Does the weary commuter really need Calatrava’s over-heated hoopla? I think not.

MODERNISM 2.0

by Witold | Feb 18, 2016 | Architects

Marcel Breuer built his second house in New Canaan, Ct., in 1951. Known as Breuer House II, it served as the family’s home until 1975 when Breuer, then 73, sold the property. The new owners hired Breuer’s longtime associate Herbert Beckhard, to enlarge the house. Over the years the house experienced more changes and was described as “essentially gutted.” By 2005 it was threatened with demolition. New owners bought the house, removed the additions, restored the interior and doubled its size with a large addition designed by Toshiko Mori. The house is currently for sale. I haven’t seen House II in its current state, but I did visit it in 1971. We had lunch with the great man, sitting on Cesca chairs around a square granite table. It was a particular treat since I had always admired Breuer’s houses, which seemed to me the epitome of what a modern house should be: simple, a bit rough—almost crude—uncluttered, less self-consciously arty than Le Corbusier, more livable than Mies. A kind of updated farm house: slate floor, plain wood ceiling, unassuming details. What a difference sixty years makes! Judging from photographs, the interior today is sleek, precise, self-conscious, expensive-looking. Not your grandfather’s modernism.

Marcel Breuer built his second house in New Canaan, Ct., in 1951. Known as Breuer House II, it served as the family’s home until 1975 when Breuer, then 73, sold the property. The new owners hired Breuer’s longtime associate Herbert Beckhard, to enlarge the house. Over the years the house experienced more changes and was described as “essentially gutted.” By 2005 it was threatened with demolition. New owners bought the house, removed the additions, restored the interior and doubled its size with a large addition designed by Toshiko Mori. The house is currently for sale. I haven’t seen House II in its current state, but I did visit it in 1971. We had lunch with the great man, sitting on Cesca chairs around a square granite table. It was a particular treat since I had always admired Breuer’s houses, which seemed to me the epitome of what a modern house should be: simple, a bit rough—almost crude—uncluttered, less self-consciously arty than Le Corbusier, more livable than Mies. A kind of updated farm house: slate floor, plain wood ceiling, unassuming details. What a difference sixty years makes! Judging from photographs, the interior today is sleek, precise, self-conscious, expensive-looking. Not your grandfather’s modernism.

SENTIMENT

by Witold | Jan 22, 2016 | Architecture

In September 1900, the office of Walter Cope and John Stewardson (who had died a few years earlier) produced a report in conjunction with their plan for the new campus for Washington University in St.Louis. The report is titled “Explanation of Drawings,” and a large part is devoted to a discussion of architectural style, specifically of Classical and Gothic. The authors argue for the latter (the firm more or less invented Collegiate Gothic), on the basis of cost, adaptability, scale, and appropriateness to an educational institution. They also point out the sentimental connection that exists between Gothic and institutions of higher learning, which evolved side by side in the Middle Ages. “If we ignore true sentiment in architecture we shall have little left,” they add. I realized when I read this that this is precisely what disturbs me about the current fashion in architectural design. Buildings have eliminated all sentiment. They may be ingenious and complex, but they are so in a way that is hermetic and self-contained. Instead of “looking like” buildings, that is, establishing a sentimental tie with the long arc of history, they merely look forward into an unknown future. Perhaps that’s why they remind me of giant appliances.

THE OBAMA LIBRARY

by Witold | Jan 10, 2016 | Architects, Architecture, Modern life

The announcement of the seven finalists for the Obama Presidential Library in Chicago is puzzling. First of all, why such an announcement at all? It has become common practice for museums and concert halls planning new buildings to draw out the architect selection process to the max. First the announcement of a competition; then revealing a short list; then the unveiling of actual designs; then the finalists; and finally—drum roll here—the winner. This process is calculated to generate the maximum amount of media coverage and publicity to assist in fund raising. This appears unnecessary—not to say unseemly—for a presidential library. Moreover, is a design competition really the best way to chose an architect for such a personal building? Obama should be choosing an architect, not a design. (An architect who understands that a presidential library is about the President, not about the architect.) But exactly what is the President looking for? The bewilderingly heterogeneous list (choose between Renzo Piano and SHoP, or between David Adjaye and Williams & Tsien) offers no answer.

LEARNING FROM MANHATTAN

by Witold | Dec 17, 2015 | Housing, Modern life

Monacelli Press has issued a new monograph on the work of Robert A. M. Stern Architects—one of a continuing series. This one is titled City Living, and it describes urban apartment houses, more than thirty of them. RAMSA is an eclectic firm, but the architectural style of these apartment towers is consistent, what New Yorkers call “prewar,” that is, pre-WWII. It appears that everybody wants “New York prewar” for the book describes built work not only in the major American cities—New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, D.C., Boston, Atlanta—but also in London, Moscow, Toronto, Lima, Shanghai, Chongqing, and Taipei. And why not? The upper-middle-class New York City apartment building of the 1920s remains the acme of civilized high-rise, high-density urban living. It successfully mediates between the street and the skyline, provides a sense of character that reflects—but does not overwhelm—its communal function, and gives the designer the freedom to lay out interesting unit plans. If you must have pencil-thin towers, and this disturbing building type seems unstoppable, then RAMSA’s 82-story 30 Park Place on Church Street in Lower Manhattan seems better than the alternatives.

LIVES OF THE ARCHITECTS

by Witold | Nov 23, 2015 | Architects, Architecture

“Architecture is the picture frame and not the picture” is a memorable quote attributed to the mid-century California modernist, William Wurster. Wurster, a notable teacher as well as an architect, was reminding his students that architecture is always a setting, not the main event. I thought of Wurster’s observation recently when I was writing an essay for Architect on the challenges of architectural biography. Why are there so few first-rate biographies of architects, I asked? Or, to put it another way, why don’t first-rate biographers such as David McCullough, Edmund Morris, and Walter Isaacson, take the life of an architect as their subject? Is it that there are simply too few readers who are interested in what architects actually do? People are fascinated by cars, for example, but they are not that interested in how—and by whom—they are designed. You can count recognizable car designers on one hand: Ferdinand Porsche (Volkswagen Beetle), Alec Issigonis (Mini), Raymond Loewy (Studebaker Commander), Harley Earl (1953 Corvette), Pinninfarina (Giulietta Spider). Similarly, people recognize iconic buildings (the White House, the Empire State, San Francisoco City Hall) without necessarily knowing—or caring—who built or designed them. Or, as a friend suggested, perhaps architects are just not that important in the overall scheme of things. After all, what would you rather read about, the person who made the picture frame, or the one who painted the picture?

“Architecture is the picture frame and not the picture” is a memorable quote attributed to the mid-century California modernist, William Wurster. Wurster, a notable teacher as well as an architect, was reminding his students that architecture is always a setting, not the main event. I thought of Wurster’s observation recently when I was writing an essay for Architect on the challenges of architectural biography. Why are there so few first-rate biographies of architects, I asked? Or, to put it another way, why don’t first-rate biographers such as David McCullough, Edmund Morris, and Walter Isaacson, take the life of an architect as their subject? Is it that there are simply too few readers who are interested in what architects actually do? People are fascinated by cars, for example, but they are not that interested in how—and by whom—they are designed. You can count recognizable car designers on one hand: Ferdinand Porsche (Volkswagen Beetle), Alec Issigonis (Mini), Raymond Loewy (Studebaker Commander), Harley Earl (1953 Corvette), Pinninfarina (Giulietta Spider). Similarly, people recognize iconic buildings (the White House, the Empire State, San Francisoco City Hall) without necessarily knowing—or caring—who built or designed them. Or, as a friend suggested, perhaps architects are just not that important in the overall scheme of things. After all, what would you rather read about, the person who made the picture frame, or the one who painted the picture?

ARCHITECTURE AHOY

by Witold | Nov 12, 2015 | Architecture, Modern life

Architects such as Norman Foster, Frank Gehry, and Zaha Hadid have been commissioned to design luxury yachts, but it is cruise ships that beg for an architect’s touch. In fact, these maritime behemoths already resemble buildings—very big buildings. Granted their designs are generally banal, but it is easy to imagine them styled by high-fashion architects. This would solve another pressing problem. Every city seems to want an iconic building designed by a starchitect. Now they could lease a floating icon instead of saddling themselves with a potential permanent eyesore. One can imagine the waterfront of Dubai, or London, or Chicago, as a maritime parking lot with the latest architectural glams. After several years, when the shine begins to fade—literally as well as figuratively—the icon ships could sail off to a lesser urb, Glasgow, or Riga, or Lagos; even an impoverished city could afford a Nouvel or a Piano for a month or two. Since the current architectural icons are largely placeless, they are perfectly suited to such a nomadic existence. At home everywhere—and nowhere.

Architects such as Norman Foster, Frank Gehry, and Zaha Hadid have been commissioned to design luxury yachts, but it is cruise ships that beg for an architect’s touch. In fact, these maritime behemoths already resemble buildings—very big buildings. Granted their designs are generally banal, but it is easy to imagine them styled by high-fashion architects. This would solve another pressing problem. Every city seems to want an iconic building designed by a starchitect. Now they could lease a floating icon instead of saddling themselves with a potential permanent eyesore. One can imagine the waterfront of Dubai, or London, or Chicago, as a maritime parking lot with the latest architectural glams. After several years, when the shine begins to fade—literally as well as figuratively—the icon ships could sail off to a lesser urb, Glasgow, or Riga, or Lagos; even an impoverished city could afford a Nouvel or a Piano for a month or two. Since the current architectural icons are largely placeless, they are perfectly suited to such a nomadic existence. At home everywhere—and nowhere.

THE LATEST