THE REAL THING

by Witold | Mar 9, 2021 | Architecture

My wife and I live in a downtown Philadelphia loft in the Larkin Building, a 12-story industrial building built in 1912-13. The builder was the Larkin Company, which a decade earlier had hired Frank Lloyd Wright to build its headquarters building in Buffalo, N.Y. Our building was designed by a lesser light. C. J. Heckman was a Buffalo-based architect about whom the internet provides no information at all. Was he the Larkin house architect, or did he simply specialize in industrial buildings, the lowest rung on the practitioner’s ladder? Perhaps the latter, because our building is a very early example of reinforced concrete construction, a 20 by 20-foot grid of mushroom columns. The building originally contained showrooms on the first floor, offices on the second, and manufacturing and warehouse floors above. Mundane uses, but in small ways Heckman gave the building some real refinement. He designed the windows to emphasize the 20-foot structural grid. As architects had been doing since ancient Greek times, he beefed up the corners. He treated the lower two floors as a “base” and introduced an external molding that turned the upper two floors—ever so subtly—into an attic (the original building had a prominent cornice, long since gone). In these ways, although Heckman was working with a new material—reinforced concrete—and a new structural system, he established links to the architectural past. At the same time as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (not yet Le Corbusier) was doodling sketches of the Dom-ino House, Heckman was building the real thing, and doing it in a way that did not upset but rather re-affirmed the old architectural verities.

HATS

by Witold | Mar 6, 2021 | Architecture, Modern life

The old Lit Brothers department store (built and expanded between 1859 and 1918) on Philadelphia’s Market Street has a sign over one of its corner entrances, that has always puzzled me. HATS TRIMMED FREE OF CHARGE is embossed into the metal fascia of the canopy. It’s the only such sign. But whose hats, men or women? Did it refer to a hat bought in the store, or was it—as I suspected—an enticement to walk in and get your hat “trimmed,” whatever that meant? And why was this procedure so important—and so common—that it had to be emblazoned over the store entrance? The Internet has many references to the sign, but I couldn’t find an explanation. The closest I got was an article on how Stetson hats were made (John B. Stetson, a native of New Jersey, not Texas, established his factory in Philadelphia in 1865). The original Stetsons were made out of felt composed of beaver fur. The last step in the manufacturing process was to sand the blocked felt to remove excess hairs. Did such felt hats require periodic sanding and “trimming.” Perhaps.

ROADBLOCKS

by Witold | Mar 3, 2021 | Architecture, Modern life

The pandemic lockdown has turned me into a podcast listener. One of my favorites is GLOP Culture, with Jonah Goldberg, Rob Long, and John Podhoretz. In a recent conversation about woke bullying at the New York Times and Slate, Long made an interesting observation. There are too many wannabe journalists chasing too few jobs. What if wokeness is simply an expression of careerism, the young finding a way to make room for themselves by pushing out the old? A recent wokey article in Architect magazine, the official journal of the AIA, approvingly describes the dean of the Princeton school of architecture characterizing professional licensure as “a gargantuan roadblock to a racially and otherwise diverse and equitable field.” Since architecture is a zero-sum game—if you get the job then I don’t—I’m not sure what “equitable” means. In any case, the architectural profession needs more roadblocks, not fewer. I once asked a colleague at the Wharton School why his MBA grads earned two or three times more than my architecture students who had actually spent a year longer in graduate school. “Your guys actually like what they do, so why should people pay them for it,” he said jokingly. More seriously, he pointed out that there were simply too many architects. When I graduated there were 6 Canadian schools of architecture; today there are 12. In the United States there are 121 accredited programs; more than 5,000 graduates every year. Too many architects; too little work.

CONVICTION

by Witold | Feb 27, 2021 | Architecture

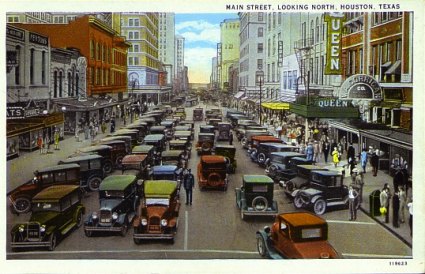

I’ve come to the conclusion that what I value most in architectural work, apart from skill and competence, is conviction. That is why I appreciate the work of Louis Kahn and his teacher Paul Cret equally, because while their work is quite different, it’s executed with a strong sense of purpose. Absent that, architecture risks becoming merely a weak-kneed copy-book reproduction, whether it is modernist or classicist. There is nothing weak-kneed about one of my favorite Philadelphia buildings, the Main Branch of the U.S. Post Office on Market and Thirtieth Street (today it houses the IRS). It was built in 1931-35 and designed by the leading local firm of Rankin & Kellogg. John Hall Rankin was a graduate of MIT and Thomas M. Kellogg had attended MIT and apprenticed with McKim, Mead & White. They formed a partnership in 1891 and acquired a national reputation after winning competitions for several prominent federal buildings. The Post Office, which covers a city block, is a five-story steel frame building clad in Indiana limestone. The flat roof was designed as a landing pad for autogyros that brought air mail from nearby airports in Camden and Philadelphia. The overall composition of the building is Beaux-Arts classicist but the style is Art Deco combined with pre-Columbian Inca motifs. Admittedly an odd combination. I always glance at the granite entrance portal as I walk by. A stylized American eagle is perched above the entrance. The curved Art Deco forms are stylishly streamlined, but they also suggest—mail boxes! The portal contrasts with the smooth limestone wall and the Pre-Columbian patterned panel above. It shouldn’t make sense but it does. That’s conviction.

THE AFTER TIME

by Witold | Feb 26, 2021 | Modern life, Urbanism

A lot has been written about the effect of Covid-19 and the associated year-long shutdown, on cities. The present situation is dispiriting: so many of the amenities that attracted people to cities in the first place—theaters, museums, ball parks, restaurants, bars—are either closed or half-closed. Too many businesses have gone out of business. Municipal tax revenue is down; municipal social costs are up. Commuting is down; crime is up. Tourism—a number one industry in many cities—is down; homelessness is up. Most urban commentators have reverted to their priors. Advocates of decentralization see a further shift to suburban living; digital seers see more work at home; downtown advocates say not to worry, it will all come back. Will it? Peggy Noonan’s contrarian column in the Wall Street Journal makes for sobering reading. “You can know something yet not fully absorb it. I think that’s happened with the pandemic. It is a year now since it settled into America and brought such damage—half a million dead, a nation in lockdown, a catastrophe for public schools. We keep saying ‘the pandemic changed everything,’ but I’m not sure we understand the words we’re saying.”

REMEMBERING

by Witold | Feb 25, 2021 | Modern life

“By convention, we erect most of our monuments to salute the heroic spirit, or acknowledge acts of sacrifice of statue-genic soldiers, police, and firefighters or illustrate national ideals, such as the Statue of Liberty or the Gateway Arch,” writes Jack Shafer in Politico, in an article that argues that we are unlikely to erect a monument to commemorate the victims of the Covid-19 pandemic. He is right, at least historically—there is no monument to the great influenza pandemic of 1918-19, although the recent trend, demonstrated by the 9/11 Memorial in Lower Manhattan, is to commemorate individual victims. Shafer reasonably suggests that a statue saluting the medical scientists who created the vaccines would be appropriate, but the year-long (and is it over?) pandemic has touched the lives of millions and deserves commemoration. The Monument to the Great Fire of London comes to mind. It was begun in 1666, five years after event. Although the death toll was small, the homes of ninety percent of Londoners were destroyed as well as numerous important buildings, including Saint Paul’s Cathedral. The Doric column, topped by an urn of fire, was designed by Christopher Wren. It was erected near the place where the fire began, but unlike so many modern memorials it doesn’t attempt to capture all the details. Instead it simply reminds us “This happened. It was important.”

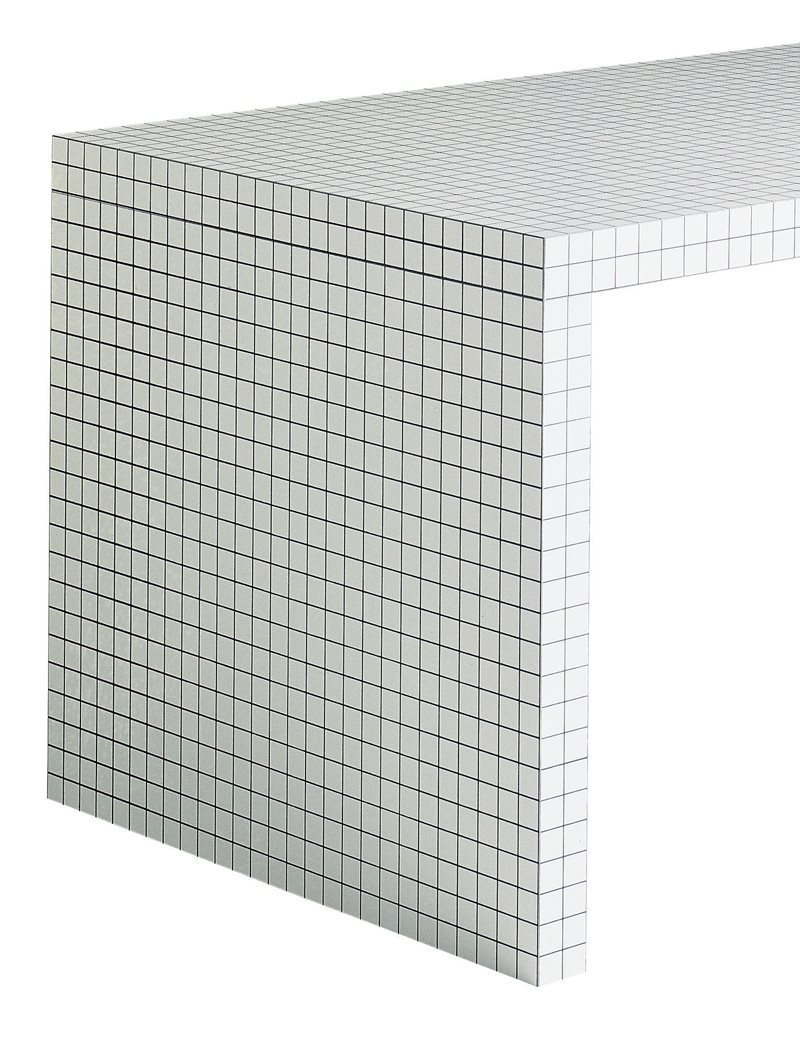

RADICAL CHIC

by Witold | Feb 16, 2021 | Architects, Architecture

The architecture group, Superstudio, was founded in Florence in 1966, the year I graduated from architecture school. I remember their projects from the Italian design mag Domus, which I used to leaf through in the library. I didn’t like them then and I don’t like them now. “Although Superstudio built very few actual buildings, its witty photo collages and designs, presented in exhibitions and glossy magazine spreads, opened up new possibilities for what architecture and urban planning could be,” opines a fawning article in the New York Times. The new possibilities included a nihilistic view of architecture masquerading as a fashionable left-wing critique. The Times quotes the last surviving member of the group: “Seeing the dystopias of your own imagination being created is not the best thing you could wish for.” But were they really dystopias? In its muddleheaded way, Superstudio (what pretension!) wanted to have its radical critique and eat it too, which may be why those early collages of implacably gridded buildings marching across the landscape influenced the work of Meier, Koolhaas, Holl, et al. Another possibility that Superstudio opened up was branding; in 1970 they designed a line of furniture for Zanotta. Gridded, of course.

MINOR FIGURES

by Witold | Feb 12, 2021 | Architecture

Philip Kennicott writes yesterday in the Washington Post about the United States Commission of Fine Arts, whose seven members are currently all Trump appointees, four appointed at the last minute on January 12, 2021. Kennicott is scathing in his evaluation: “The original members, and the vast majority of those who followed them over the past 110 years, were giants in their field, while the Trump appointees who now run the CFA are minor figures, chosen not for their accomplishment but for their ideological conformity to a rigid doctrine of architectural classicism.” Kennicott’s point about ideological conformity is important. When I served on the Commission (2004-12) it included a variety of accomplished architects, landscape architects, and artists—Michael McKinnell, Diana Balmori, David Childs, John Belle, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Teresita Fernández, Philip Freelon, Elyn Zimmerman, and Pamela Nelson. Our chair, Rusty Powell, had the art historian’s—and the Washington insider’s—long view. We had different tastes and different philosophies but the differences were accompanied by a sense of mutual respect. As a result we were able to usefully review projects by widely dissimilar architects and designers: Frank Gehry, Kevin Roche, James Polshek, Richard Rogers, David Schwarz, Norman Foster, Bing Thom, David Adjaye, Warren Cox, Laurie Olin, and Elizabeth Diller.

Kennicott’s second point about “minor figures” is likewise important. While the CFA has design approval authority in certain defined areas, it generally operates in an advisory capacity, that is, on the basis of moral suasion. This influence depends entirely on the reputations of the commissioners. “The Trump appointments to the CFA would effectively make the group useless and could lead to its demise,” writes Kennicott. His conclusion? “President Biden should move quickly to remove the current members.” A drastic suggestion that flies in the face of tradition—no CFA commissioner has ever been thus removed—but one that is warranted in this case.

Photo: Seal designed by Lee Lawrie, 1950

FECKLESS FORUM

by Witold | Dec 18, 2020 | Architecture

The New York Times reports on the opening of the Humboldt Forum, a new Museum in Berlin. When I showed the photograph (left) to my wife her reaction was “It looks like a prison.” She wasn’t referring to the Baroque facade, of course. I haven’t seen the museum, but the photograph is like a beauty contest—Baroque vs Modernist—and it’s pretty obvious who is the winner. The Forum sits on the site of the Berliner Schloss, the immense royal palace that had been greatly expanded by Frederick the Great in the early 18th century and whose dome was based on a design by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. The Schloss, which is considered one of the great works of Prussian Baroque architecture, was damaged in the Second World War, and in 1950, the East German government entirely demolished the building (it took 19 tons of dynamite) and replaced it with the Palast der Republik, a modernist building housing the GDR parliament. After German reunification, the Palast was torn down and it was decided to re-build the original 18th-century palace. Although the Times reporter referred to the new building disparagingly as a “facsimile,” there is a long tradition of restoring damaged or destroyed buildings (the medieval St Mark’s Campanile in Venice was rebuilt in 1912 after collapsing). The Campanile was entirely restored, but the Berlin restoration is partial. Three of the four facades are Baroque, the fourth is modernist, and the same strategy governs the design on the interior courts (see photo). It is an oddly half-hearted approach to restoration that has pleased neither traditionalists nor modernists.

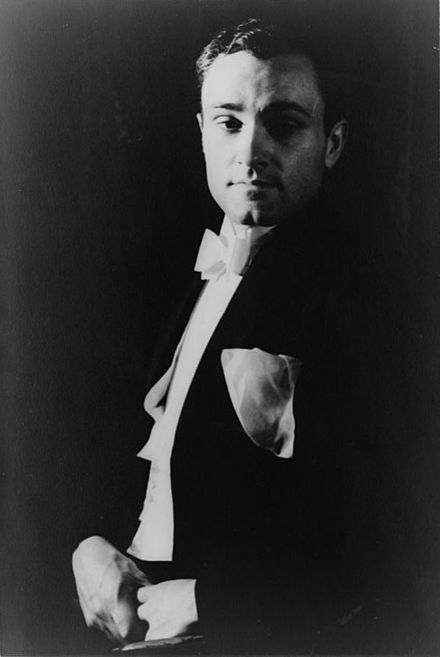

YES, BUT . . .

by Witold | Dec 9, 2020 | Architects

“The test of a first-rate intelligence,” famously said F. Scott Fitzgerald, “is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” In Philip Johnson’s New York Times obituary, Paul Goldberger described him as architecture’s “godfather, gadfly, scholar, patron, critic, curator, and cheerleader.”That is true. It is also true that although Johnson rejected Nazism after the end of the Second World War, in his younger years he attended Nazi rallies in Germany, admired Mein Kampf, and had connections to the Nazi party. Can Johnson be celebrated for the first activities and condemned for the second? Apparently not. A public Instagram letter from the largely anonymous Johnson Study Group. demands that with the purpose of “dismantling of white supremacy” MoMA and the GSD remove Johnson’s name from titles and spaces, which include the title of the museum’s chief curator of architecture and design, the department that Johnson founded, as well as the house (now owned by Harvard) that Johnson built in Cambridge. In other words, Mr. Johnson is to be cancelled.

THE LATEST