I’ve been researching Marcel Breuer in connection with a new book. The 18-year-old Breuer started as an art student in Vienna, then transferred to the new Bauhaus in Weimar. He chose the woodworking program, and proved to be so talented in furniture design that after he graduated Walter Gropius invited him back to be the master of the woodworking shop. In one short period, 1925-30, Breuer designed some of the seminal modernist chairs of the twentieth century: the Wassily, the Cesca, the B35 lounge chair. During the 1930s, he started working as an architect, collaborating with F.R.S. Yorke in UK and Gropius in the US, and finally working on his own. What is striking is that Breuer moved so effortlessly from designing chairs to designing buildings. This is explained in two ways. Breuer had completely absorbed Gropius’s teaching that design was a universal discipline, that is, if you could design a teacup you could design a city. So having no formal training in building design or construction whatsoever (the Bauhaus did not teach architecture until long after Breuer was there), did not discourage him from undertaking building commissions. The second reason is that modernist architects were inventing as they went along; they did not rely on history, traditional construction, or conventional building practice. Hence, the lack of training was not a liability. Just as a tubular steel lounge chair had no precedent, so too a glass and concrete building was breaking new ground. It was all new.

Of course, such an improvised art could not last. By the late 1950s, as modernism became an academically entrenched discipline—instead of an avocation—it began to show signs of flagging. You can’t really teach improvisation, any more than you can teach jazz. Neither modern jazz nor modern architecture survived.

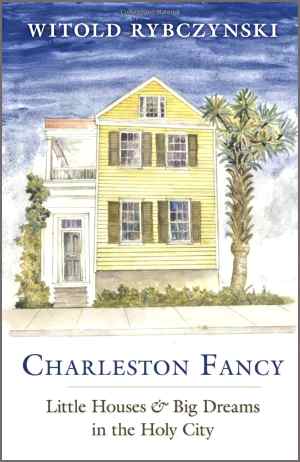

I have 2 of the marcel breuer Thonet tubular reed lounge chairs available, the type is as shown in your photo above. They have been in my possession since 1974. Thonet labels are intact. In daily use since then.